Through the courtesy of Flavia Cuevas it was possible to obtain lodging at the eco-lodge, Hacienda San Lucas. This is on the mountain overlooking the Copan river. The Hacienda San Lucas is a few kilometers from the village of Copan Ruinas, Honduras, Central America.

The manager of the eco-lodge suggested we should visit Los Sapos. She kindly took us there personally.

Los Sapos is an area where the natural bedrock has been carved into three main scenes:

- A seated sapo (frog or toad)

- A crocodilian creature (head and torso only; not the entire body)

- A person who may be cutting his enlarged phallus

There is also an area of mounds a few meters away. But we came primarily to see the bedrock sculptures. Fortunately the sunlight was at a pretty good angle, so we were able to photograph the amphibian and crocodilian. The fat person with probable phallus was not as easy to photograph since better lighting would have been raking light (so would need an electric generator and portable studio lights).

|

Image of maya sculptures at Copan, Honduras. April 2012

|

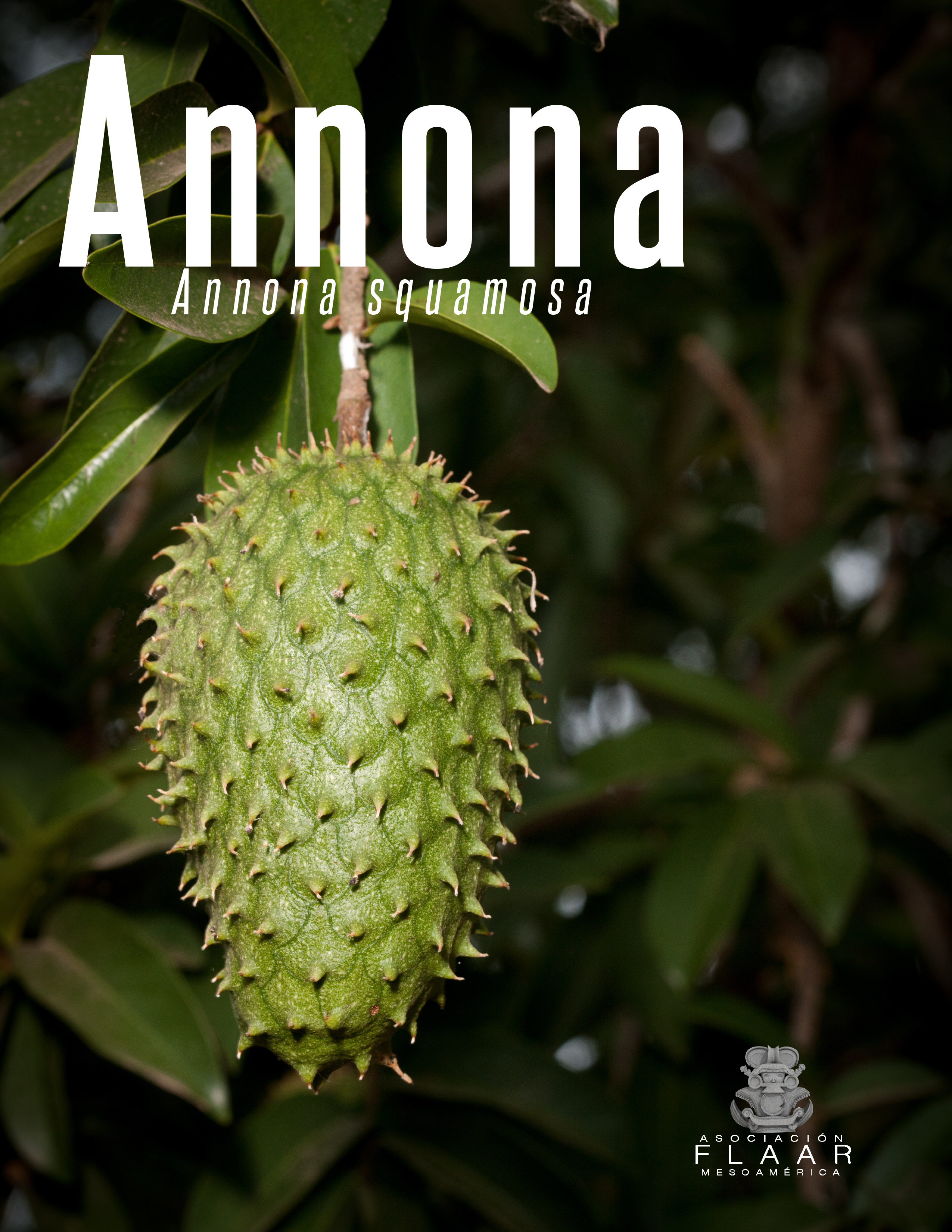

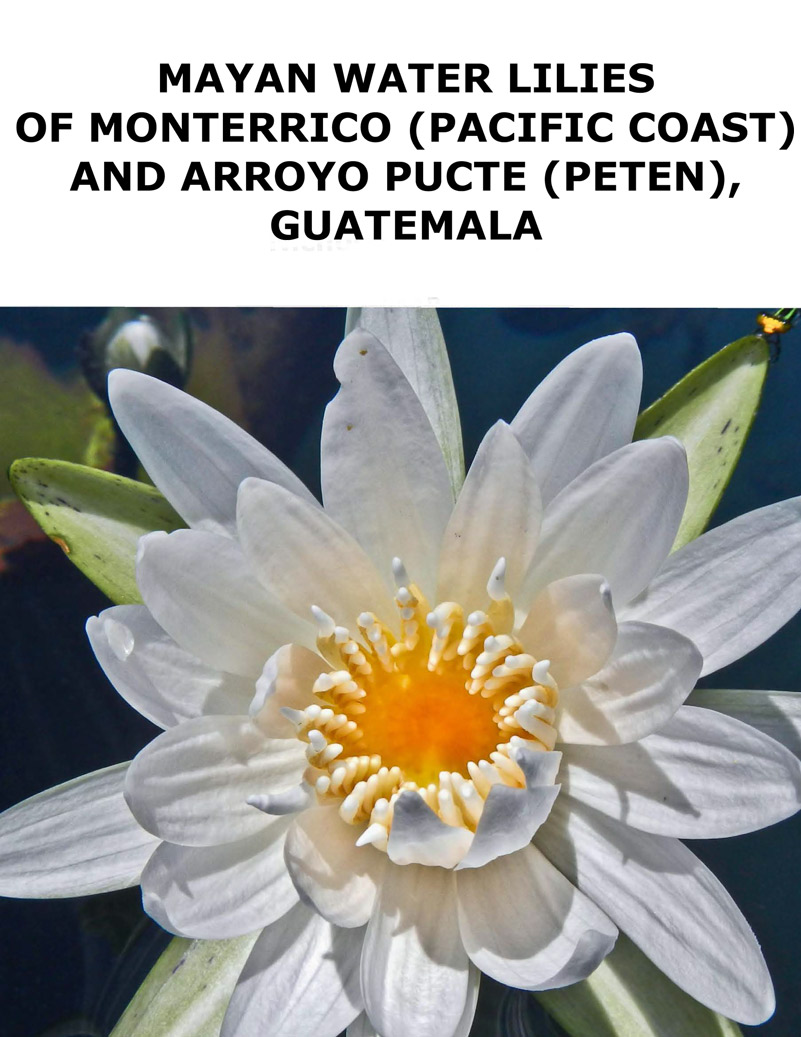

There are two main kinds of toads which were important in Maya iconography

- Bufo marinus (and a close relative, Bufo valliceps) is the main amphibian in the art and mythology of the Maya and their neighbors.

- Burrowing toad, Rhinophrynus dorsalis

The burrowing toad is not the creature pictured here at Los Sapos

The burrowing toad is not the species sculpted in the bedrock here at Los Sapos. The burrowing toad is like a blob of jello. The limbs and other body parts you would expect on a normal frog or toad are not as evident on the uo. A uo toad is literally a blob of jello-like consistency.

Because the uo spends most of its life underground, we do not have photographs of it in recent times. I have experienced "the night of the uo" at Tikal but photographs from that far back are not well preserved.

|

Angle view of a toad scultpure at Copan, Honduras. April 2012

|

Bufo marinus and Bufo valliceps are easier to see in most parts of Guatemala and I would estimate also in many parts of Honduras. These toads are sufficiently common that they are relatively easy to photograph. These Bufo species are of significant interest in Maya diet (yes), in Maya beliefs, and in Maya art. So we have separate reports on the creatures themselves. They actually make nice pets but it is not friendly to keep them inside, or in a cage. Keep them outside in an area with plenty of vegetation and lots of water so they can make themselves at home.

Just realize that Bufo marinus can dig their way out of anywhere you put them. And don't keep them near children or dogs: these toads are extremely venomous. I handle them without gloves since they realize I am not going to hurt them. But a child or dog, if they ingest even a drop of the liquid, they will wish they died more quickly then the prolonged agony that they will face.

Toads are also found as effigy containers in Maya ceramics

Several areas of the Maya culture had a tradition to render three-dimensional effigies of toads in life-sized ceramic containers. You can find these in Honduras, Belize, Guatemala, and Mexico. But this specific page is dedicated to the Los Sapos sculptures near Copan Ruinas, Honduras.

Statues of toads in Maya art are of enormous size

Preclassic status of toads from Kaminaljuyu and related early proto-Maya sites are up to a meter in maximum dimension. So clearly the Bufo marinus was important enough in Maya religion or beliefs to create such large renditions. You can find some renditions of toads in Lee Parsons monograph on Kaminaljuyu sculpture (1986).

The most monumental rendition of a sacred toad in the art of the Classic Maya is Quirigua Zoomorph G (Monument 7). The helpful University of Pennsylvania publication has a few nice photographs but no line drawing whatsoever. The author suggests it is a feline (Sharer 1990:43). This suggestion is based on the spots on the shoulder of the creature. But if you are familiar with felines, in-person, and especially if you are familiar with Bufo marinus, up close and in-person, you would recognize the spots on Quirigua Zoomorph G as the natural patterns on the raised poison glands of the toad.

Yes, surely the Classic Maya also "saw" or "read into" these spots a feline. Indeed the claws look more like a carnivore than an innocent river-side toad. But the creature is based on a Bufo marinus not on a feline.

|

|

We began as naïve as any North American scholar who ventures into a complex eco-system such as the areas occupied by Mayan-speaking peoples. First we work for decades to learn the ancient culture. But most Mayanists have full-time teaching positions and with a family, so they can't really get out in the field as much as is really needed. I prefer to learn in-person, with the toads directly.

|

|

I have done the same with felines (studied them in-person), but the last feline I was arm-in-arm with, the photographer was so afraid the puma would eat me, that he forgot to focus the camera. I also suspect that he was afraid the puma would enjoy him for desert after digesting me. So I regret I don't have photos of me with fully-grown felines. |

Toad or frog in the sculpture of Copan: Altar O (CPN 28)

This sculpture has an overhead view of a large frog or toad with a fish behind it. Lots of carnivorous fish probably enjoyed meals of young toads and frogs. Or sometimes the Maya are just showing a watery environment. Although the Bufo marinus is a creature of the land, it does enjoy being near water: either a stream, pond, or lake.

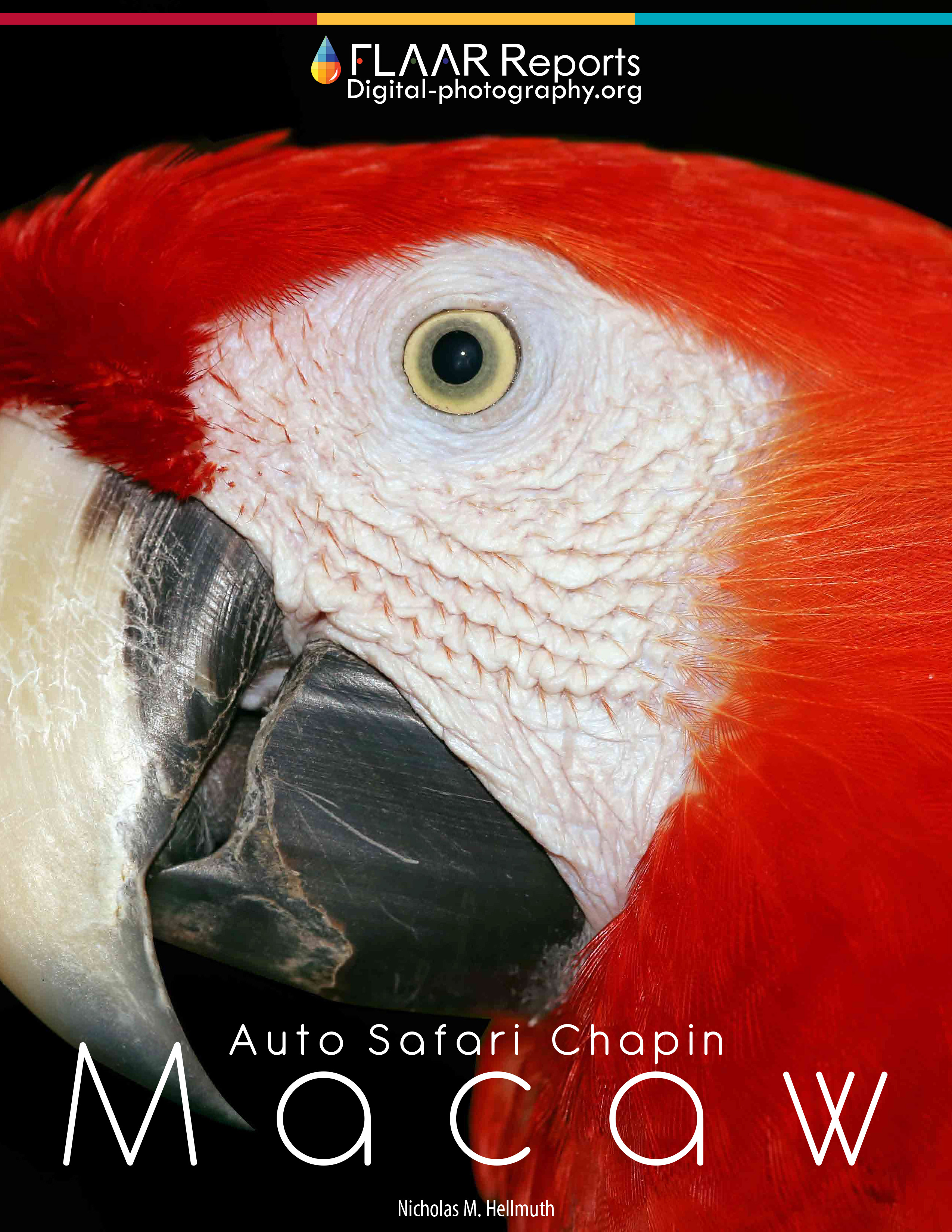

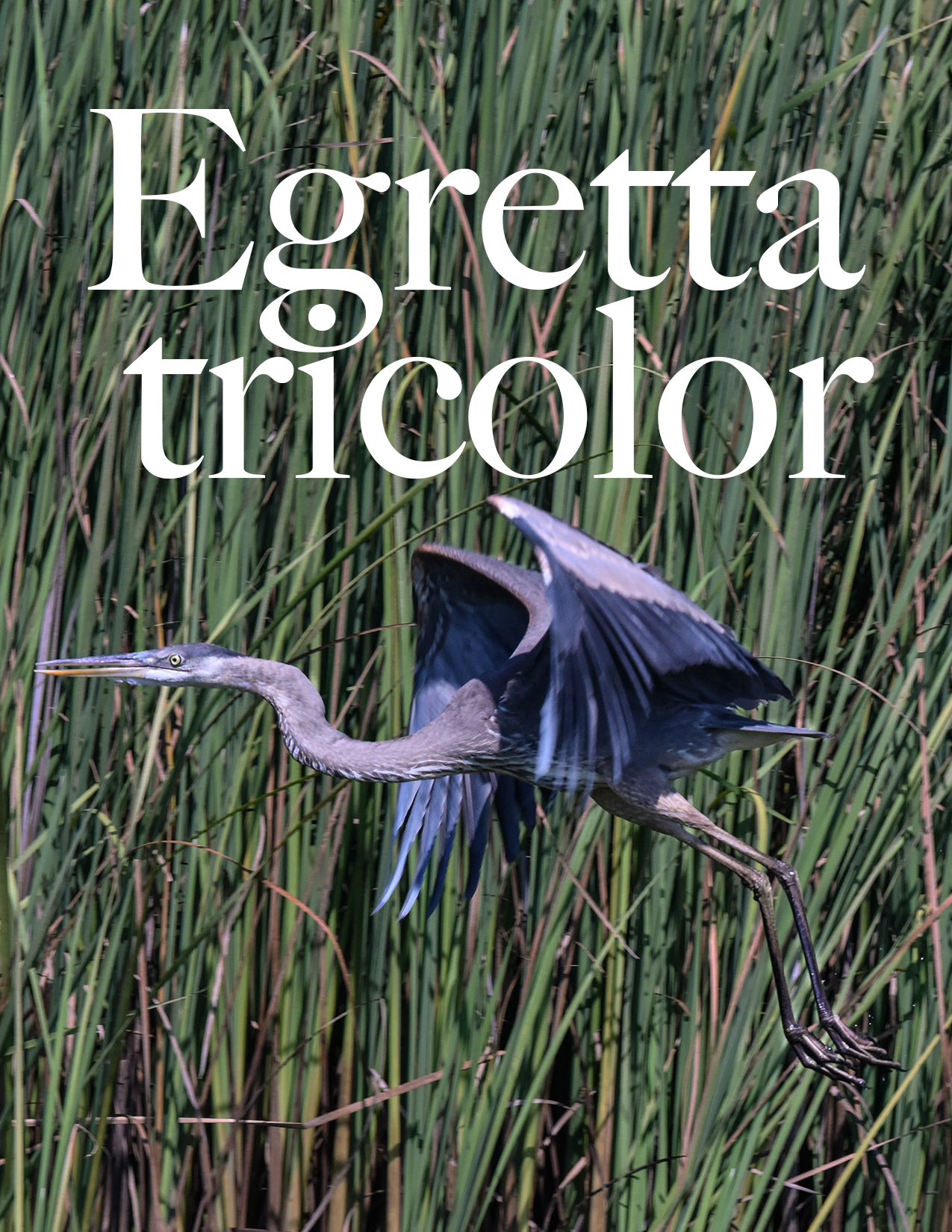

Second bedrock sculpture of Los Sapos: Crocodiles in Maya art

We have been studying crocodiles for decades since I write about them in my PhD dissertation. We have worked together with several zoological organizations in Guatemala, such as CECON, to photograph crocodiles and alligators. There are two species of crocodile and one species of alligator in the Maya area (a caiman). We cover crocodiles in separate reports.

|

Crocodile face and torso sculptures at Copan. Honduras

|

Penis perforation

There are plenty of articles about penis perforation in Classic Maya culture. There are polychrome vases which document penis perforation really was a common practice. And the king of Tikal whose royal tomb I discovered in 1965, the ruler had two penis perforators next to his phallus (which was a piece of solid jade). Stingray spines were the most common penis perforators.

Since the phallus and associated person were not well illuminated, I did not study them. Our interest at FLAAR Reports is primarily plants and animals, so the toad and crocodile were what we came to see.

Archaeology of Los Sapos

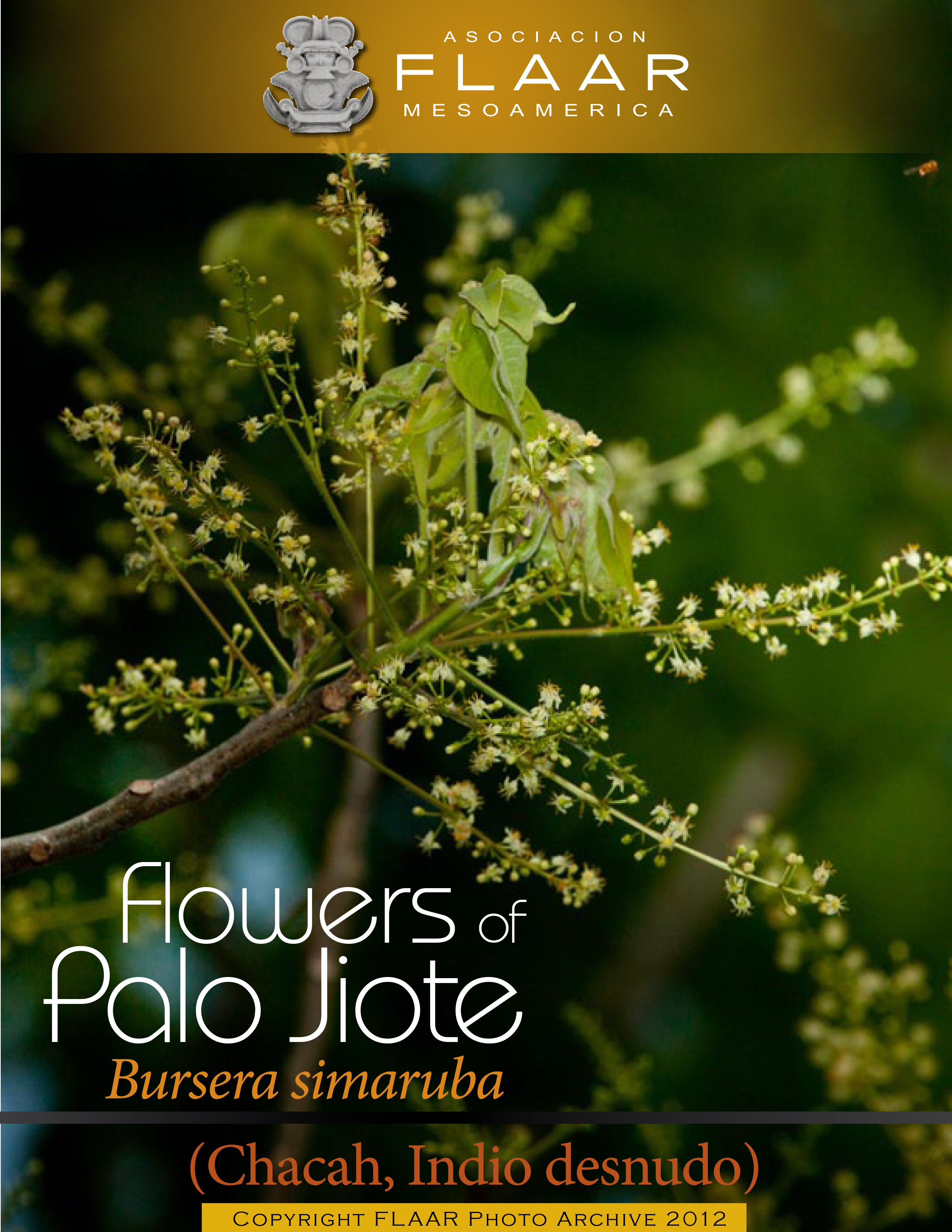

The Peabody Museum, Harvard, had a summer field school project at Los Sapos in 2001. Obviously many archaeologists before that have visited this interesting area of rock outcarvings. But our visit was not an archaeological project: we are studying plants and animals of Mesoamerica; the Hacienda San Lucas had several interested species of trees flowering this particular month (mid-April). We went to Los Sapos primarily to see the toad sculpture.

We appreciate the access to Los Sapos courtesy of Hacienda San Lucas

I have been visiting Copan since I was 17 or 18 years old. And every four or five years I have done photography of the site which we have donated to the Instituto Hondurano de Antropologia e Historia (IHAH). But I never reached Los Sapos until the Spanish archaeologist who is manager at Hacienda San Lucas told me about the place and took four of us from FLAAR there in-person.

How to get here: to Los Sapos, near Copan Ruinas village

We saw a gringo family walking here, and back, from Copan village. Very impressive, as it's straight uphill most of the way; and then more up and down hiking once you reach the property of the eco-lodge Hacienda San Lucas. One way must be three kilometers or more.

Unless you are totally out of money I would not suggest walking (too long; will simply wear you out) unless; unless you really want to experience Honduras rural areas and have plenty of time available.

Be sure to ask permission of the Hacienda San Lucas, since the entry is on their property.

And do not walk on the sculptures themselves.

Brief bibliography on toads in Classic and Preclassic Maya art

- 1994

- Maya Sculpture of Copan: The Iconography. University of Oklahoma Press.

- 1986

- The Origins of Maya Art: Monumental Stone Sculpture of Kaminaljuyu, Guatemala and the Southern Pacific Coast. Studies in Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology No. 28, Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.

- 1990

- Quirigua: A Classic Maya Center & its Sculptures. Carolina Academic Press, Durham, North Carolina.

Updated October 2020

First posted April 17, 2012.