Mayan ethnohistory is the study of the Mayan-speaking people of Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador from historical documents. These may be written historical documents such as written by Andres de Avendano, Villagutierre of past centuries, or more recent books by authors of the Carnegie Institution of Washington (such as Scholes). Lawrence Feldman would be a good example of a capable ethnohistorian of Mayan ethnohistory of recent years.

Ethnohistorical information is also harvested from handwritten manuscripts preserved in archives.

Ethnohistory is the study of any society or culture using historical sources. The sources are usually written rather than verbal. Ethnohistory tends to be the study of a people of past centuries.

I use the spelling Mayan since I do research on the people who speak the Mayan languages. The term used at universities is Maya, both as noun and as adjective. The snag in using either is that there are several Mayan languages called Maya. Yucatec Maya and Lacandon Maya are two such languages. Since the Itza of El Peten Guatemala came from Yucatan, I would estimate that the Itza speak Itza Maya (only a few still speak this language).

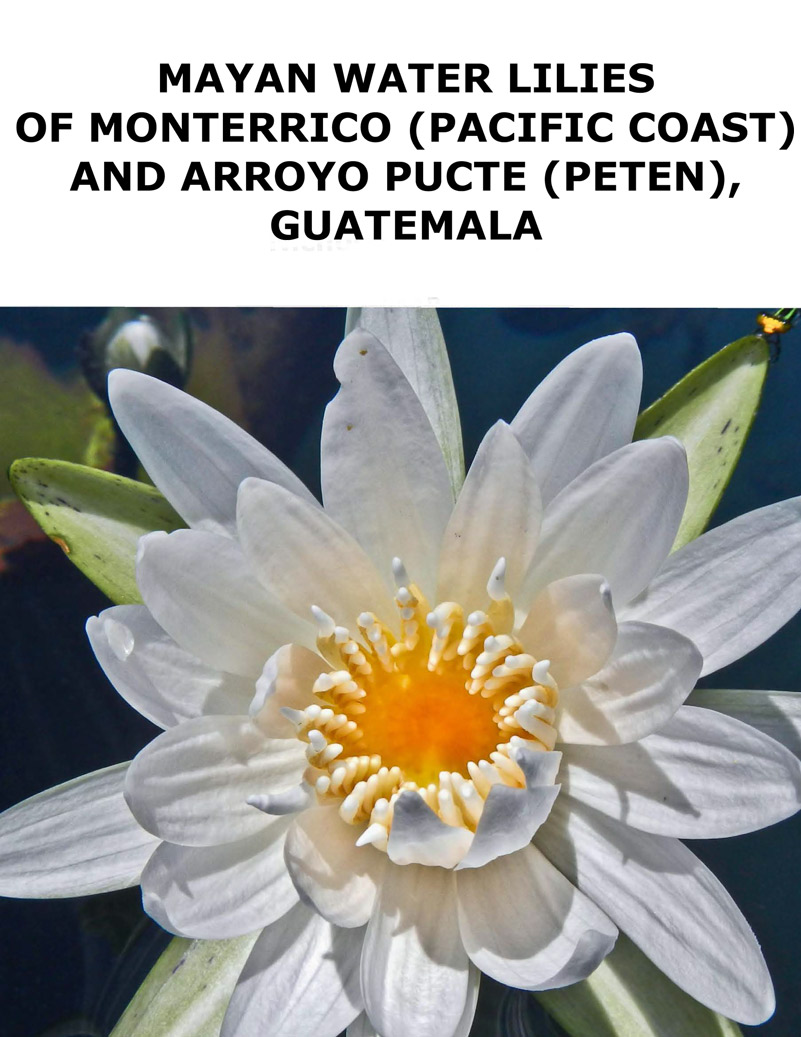

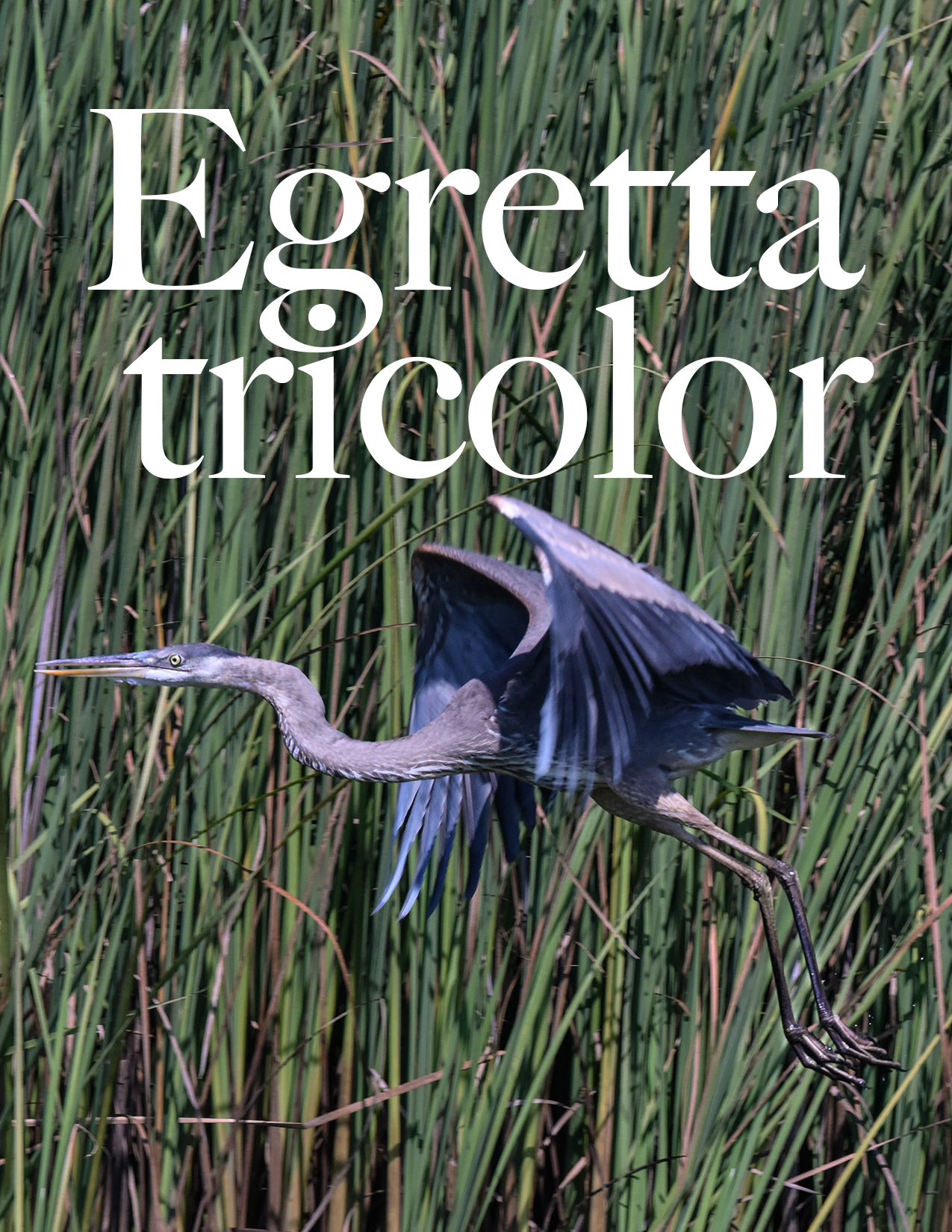

Ethnohistory is the source of frankly remarkable knowledge about the way of life of Mayan people before so much was destroyed or changed by the Spanish conquest. I was an ethnohistorian before I was an iconographer: I spent many years doing research on the Maya of Chiapas, El Peten, and Alta Verapaz. Now (today in 2017, and for the last many years), I do botanical and zoological research: studying the plants and animals of the diverse eco-systems of Guatemala.

Now lets return to ethnohistory and look at the first publication of my work, written in the late 1960’s and published in 1970. As a service to students, scholars, and interested lay people, we make this book available, at no cost, as a free download on this web site of FLAAR.

Bibliography of 16th-20th century Maya, Southern Lowlands, Chol, Chol Lacandon, Yucatec Lacandon, Itza, and Mopan

|

Inside title page from Katunob edition.

|

Inside title page from University Museum edition.

|

The bibliography was published in two editions. First came the Katunob edition, April 1970.

Then in May came an edition as Occasional Publications in Anthropology, Archaeology Series, No. 2, University of Northern Colorado, Museum of Anthropology, Greeley, Colorado. As far as I can tell they are identical except for the front cover.

Today I would call the 17th century culture the Cholti Lacandon rather than the Chol Lacandon, but Chol at least distinguishes the original inhabitations from the present-day Yucatec Lacandon. Cholti is an extinct Mayan language (the Spanish massacred most of the population which had not died earlier from infectious diseases introduced during the conquest). The few Cholti Lacandon who survived were forced to move to several areas of what is now Guatemala.

Ironically, “the Lacandon” are still spoken about in whispers in Rabinal. Many people believe that in wild areas of the mountains of Rabinal that Lacandon people still live. It would be helpful if a student who knows Achi Mayan language, and who has or can learn about the forced resettlement of the Cholti Lacandon to Rabinal (and other areas of Highland Guatemala) could do a thesis or dissertation on this subject.

Additional studies of the Lacandon

Would be nice to update this bibliography from 1969 through 2017, but without donations this much research would not be realistic. But one recent publication is definitely worth mentioning, that of Suzanne Cook, on the ethnobotany of the present-day Yucatec speaking Lacandon Maya.

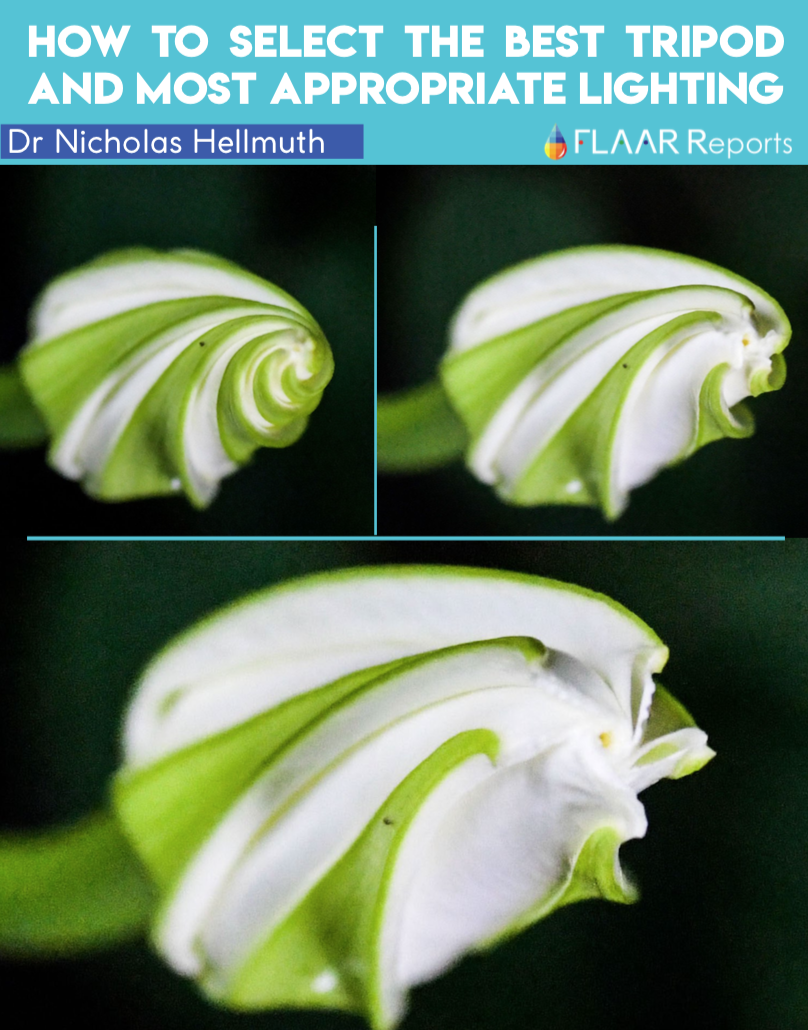

Caution about misidentifications of plants of the Yucatec Lacandon Maya

J. Eric S. Thompson was convinced that the Kin glyph was based on the Plumeria flower. Snag is that the Kin glyph is a 4-petaled flower and Plumeria have many petals. Plumeria is frangipani, and the flower often used as a lei to visitors to Hawaii many years back (now you probably get plastic fantastic if anything).

I raise Plumeria and have studied it for over five years in many eco-systems in Guatemala. I have also sought out every single 4-petaled flower which exist. The Kin hieroglyph has no need whatsoever for the Plumeria.

Unfortunately, endless epigraphers, ethnographers, and archaeologists have repeated the Plumeria error, and have compounded it with mistranslations of sac nicte so that flaws run deep in most ethnobotanical studies.

Second common misinterpretation; that people who worship in Yaxchilan or Palenque are the descendants of the original inhabitations there.

Any book, article, web site which proclaims that any Maya speaking people of today are the descendants of the builders of Palenque or Yaxchilan are repeating a popular myth. Palenque descendant DNA may well be in the Chol people, but not in any group who speak Yucatec Maya. Very simple: do a DNA test of all the skeletons from Palenque; then do a DNA test of 100 Chol-speaking people (and 100 Lacandon Maya). See who are the descendants.

Same for Yaxchilan: DNA, very simple (though the DNA of the elite is unlikely always the same as the DNA of farmers and workers a thousand years ago, because the elite often married royal women of royal families from far-away other Maya cities).

Anyone who speaks Yucatec Maya, of whatever dialect, came from Yucatan, whether in the 12th century (whenever it was that the Ytza moved from Chichen Itza to the island of Flores, Peten, Guatemala), or in the 16th century when Spanish oppression and cruelty pushed people out of Campeche and southern Yucatan to fill the void created when the Spanish massacred and forcibly moved out the actual inhabitations of the “Lacandon area” of Lowland Chiapas.

I dedicated many years of my life to studying the Lacandon Maya: both Cholti and Yucatec

I visited Nabolom many times in the late 1960’s and 1970’s and appreciated the hospitality of Trudy Blom. The first time I was in San Cristobal her husband, archaeologist Frans Blom, was passing away, so I waited to another year to knock on the door. Their work, and of all ethnographers, linguists, and ethnobotanists, has been helpful to world scholarship. Just that there is always a tad of a grain of romanticism in some of the discussions.

At age 17 I was already at a Lacandon village, flying in from Tenosique with the INAH team heading to Bonampak. I had been in Palenque the year before, at age 16, and returned to high school where I did my thesis on my feelings about what I had experienced at Palenque in those days (hotel cost 50 cents a night and had a bucket under the bed to put your fertilizer in). No highways, you had to come in by train and then hitch a ride to the town of Palenque.

My high school thesis about the Maya of Palenque won first prize, and with that money I returned to Mexico to explore more ruins. While in Tenosique I met the INAH archaeologists who happened to stay at the same hotel I was at (probably in the 1960’s was the only hotel in town!). I volunteered to help them carry supplies in and to assist in setting up camp, so they kindly took me along.

We flew to an airfield and then hiked on trails and through rivers for several hours. Was a great experience. After a week or so I thanked them for allowing me to have this opportunity, and I headed off for other Mayan sites. Every summer I came back to Mesoamerica, and two years in a row visited Tikal. The archaeologists there noticed I spent a week each time, so they asked me if I would like to volunteer to help them the next season. WOW, what an opportunity, at age 19 to escape reality and live in the Peten rain forest for 12 months. So I took a year off from Harvard, spent a year at Tikal, uncovering the Tomb of the Jade Jaguar in a pyramid facing the south side of Temple II. This was my Harvard thesis.

Now I am still learning about Mayan cultures, focusing for recent years on the plants and animals. The learning process is never ending since each eco-system had different plants available.

After getting an MA from Brown University (iconography of Teotihuacan and its influence on the Maya of Guatemala), I returned to Guatemala and spent as much time as possible in the Archivo General de Indias. It was tough to see a dump truck pull up and see librarians using shovels to throw out rotted documents from past centuries. So I took as many notes as possible, and based on what I found, I applied for a grant with the American Philosophical Society which got me into the Archivo General de Indias, in Seville, Spain. So by 1972 I was deep into ethnohistory and enjoyed every month’s research.

By 1977 I published my summary on the Cholti-Lacandon of Sac Balam. We have scanned this and will be issuing this as a PDF as well.

Unfortunately I do not have all my ethnohistorical notes available because our office is not large enough. My library and notes from a decade in Graz, Austria, weighed several metric tons (we learned that when we shipped all my library and notes circa 2015, on loan, to a future library of another project in Guatemala). What would be helpful is scanning all my notes from the 1970’s and having them all available for students and scholars. Donations to FLAAR are always appreciated.

This bibliography is a result of a term paper while a student at Harvard

I took a course in Mayan ethnography or comparable (hard to remember the name of a course over 50 years ago). My term paper was on the Lacandon Maya of Chiapas (since I had been in Chiapas several times, including my first trip as a backpacker in 1962).

The graduate student (teaching assistant) returned my paper to me because he said I had failed to understand the difference between the Cholti-speaking Lacandon of the 16th-17th centuries and the Yucatec-speaking Lacandon of the 18th century to the present. He suggested I should rewrite the term paper.

The professor of the course was Dr Evon Z Vogt. Graduate students handle the undergraduate students. Jeremy Sabloff was one I remember, but don’t remember whether he was the individual whose helpful reprimand got me started into many years of ethnohistorical research.

Since I had the entire Peabody Museum library accessible to me (the Tozzer Library) and since the pleasant librarian let me enter the shelves any time I wanted to, I spent a lot of time teaching myself about the various Mayan cultural groups of the 16th century and how the linguistic areas of today are a bit different.

I did so much research that I decided to submit my blbliography as a publication. So my work of the late 1960’s is now available as a digital download since 2016.

This PowerPoint lecture is potentially the first ethnobotanical identification of the 4-petaled flowers on Tepeu 2 (Late Classic) bowls, plates, and vases of Tikal, Uaxactun and related Maya sites of Peten, Guatemala.

If you would like Dr Nicholas Hellmuth to present a lecture (s) on Mayan ethnobotany, and/or on the Tomb of the Jade Jaguar, he can present in English, Spanish, or German (or you can have simultaneously translated in your home city). He has lectured in Tokyo, Seoul, Beijing, Dubai, Johannesburg, Zurich, Cambridge (UK, and also Cambridge Mass), UCLA, and museums around the world: Guatemala, Mexico, etc.

You can ask for a lecture in your home town college, university, museum, alumni club (Nicholas was a student at Harvard, Brown, and had several post-graduate research positions at Yale University), or even in your own house or your business headquarters or local club. Round trip airfare, local accommodations, airport transfer, and a helpful donation to the research of FLAAR are appreciated.

Contact: FrontDesk “at” FLAAR.org

|

Note that we are making all our PDFs to be easy to use by students and Mayanists. So we allow the PDF to be copy-and-pastable, so you can copy-and-paste any of the bibliographic entries. (we hope this works in your software). When a PDF is locked or the scan of an entire page is an “image” you can’t get into it with copy-and-paste tool.

Updated mid-February 2017.

First posted February 16, 2016.