Macaws tend to be on the sides of basal flange bowls. On some occasions you could expect macaws on the lids. In some cases you could find a macaw also as a lid handle.

If on the side of a basal flange bowl, the macaw image tends to be very stylized. If stylized in some cases would be a challenge to tell for sure whether it was a parrot or a macaw. I

In general, Maya rendition of animals (and insects and flowers), especially on Early Classic basal flange bowls and tetrapods, tend to be stylized: some features are emphasized; other features are not present.

Yes, you can occasionally find wonderful naturalistic renderings of birds in Maya art. But whereas some jaguars are clearly jaguars, if the painter is showing only a band of spots, you have to compare the spot pattern with margays, ocelots, and also jaguars to know for sure which species is really intended. And then often you find the painter is literally just showing “generic feline spots” with no scientific rendition of size, shape, or pattern of the spots of any one particular animal (each part of a jaguar body has spots of a different size, shape, and pattern).

The Maya also tend to add features to some animals which either are not found in nature at all, or are standardized “statements”, like a stylized symbol which any contemporaneous Maya would have been able to read and understand.

For example, on a basal flange bowl lid, the macaw has a dotted coil under the eye. The totally different species of bird next to it has the same coil (the other bird is not yet identified but is neither a macaw nor a parrot).

Another feature on many (and often most) birds in Classic Maya art are the profile “serpent face” wings. I temporarily call it a serpent face; If you spent several years searching for, and tabulating the details of all such bird wing faces, surely a better term could be devised. And perhaps it may be possible to differentiate different species of these wings. But that is not the goal, here I just wish to comment that most representations of birds, and especially many images of macaws, have these symbolic wing feather patterns arranged into a reptilian face (complete with nose and nose beads).

The first comment might be that such serpent faces are merely tacked onto the birds. But in actuality, the serpent face is a design which is actually physically on the underside of many natural species of birds. It would be a great thesis or dissertation to study the under-wing feather and bone structure pattern of all major birds of the Maya area to see which bird was the inspiration for such a profile reptilian facial design: quetzal, macaw, eagle, or other.

Rendition on signage within Copan Ruinas area, Honduras. This method of crossing the necks of two species of birds is how the Maya sometimes show two different bird species in the Early Classic (circa AD 200-300).

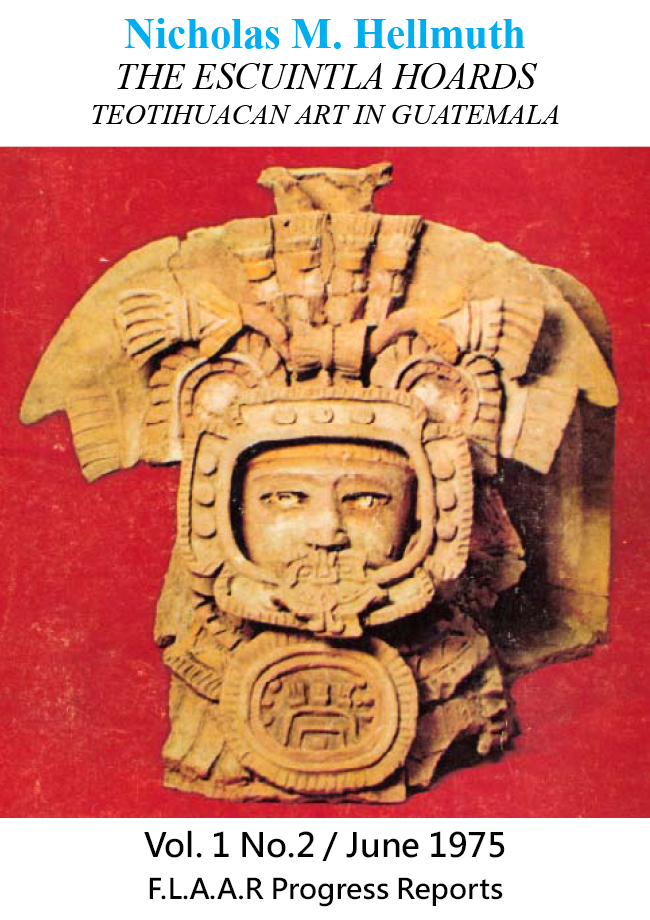

Rendition of the macaw beak in Maya art

An actual scarlet macaw beak has two black areas: the entire lower beak and a triangle on the part of the upper beak that touches on the black lower beak. On the stylized macaw the lower beak is highly stylized, almost like a tongue, but is black. The adjacent part of the upper beak is black, but in two segments.

The upper beak on the painted macaw has an “air hole” of much bigger size than the original. The beak itself is curved down like an elephant trunk. Indeed many popular writers have misidentified the shape on Copan Stela B as an elephant trunk. Fortunately Maya scholars were generally not falling into the elephant misinterpretation. But anyone whose agenda is to “show” influence from Asian or African culture loves to (mis)use the “elephant trunks” to “prove” the foreign influence.

On the Tzakol rendition, the eye of an actual macaw is small, and is towards the top of a circular white area which is pure skin (devoid of feathers). On the painted Tzakol macaw the eye is large (like a modern cartoon, but not as bulbous as a cartoon eye). In the painting the eye is at the bottom of the featherless area.

Macaws and Parrots on Basal Flange Bowls

You could find dozens of macaw-like or parrot-like birds, highly-stylized, on Tzakol pottery. These birds may be on the outside or inside. Ironic that the corpus found by the University of Pennsylvania had very few.

Same with the Uaxactun project of CIW: only the tail feathers of one (Fig. 28, 8) and just two complete stylized examples (Fig. 28, 3 and4). I am estimating these birds are macaws since common parrots are less often shown.

For the El Mirador area, you can find examples in the thesis of Ordóñez (2012:25, 28). Unfortunately, most large Maya archaeology projects no longer have a thorough complete monograph on ceramics: Uaxactun and Tikal are the best examples of adequate write-up of the ceramics after field work. But where are comparable volumes for all the other recent and current archaeological projects?

Macaws on ballgame hachas, especially of Guatemala

It is ironic that the origin of the ballgame hacha concept is supposedly Classic Veracruz area, but in fact you find more ballgame hachas and ballgame yokes in Guatemala (especially in the Costa Sur area). I estimate that most of these ballgame accessories are earlier than the Bilbao, Cotzumalhuapa culture, but sorting out ballgame yokes and hachas would require a PhD dissertation.

In the meantime, the monograph by Shook and Marquis shows more macaw-related ballgame hachas than any other monograph. She specifically avoids wading into the quagmire of figuring out which are parrots and which are macaws, but I estimate that most of the 16 hachas show a scarlet macaw head and beak. There is also one monkey hacha with a macaw top beak in front of the monkey head (M32, page 157) and on the front of an aged generic only partially-avian face (H81, page 127).

I have not previously seen much mention of macaw ballgame hachas in studies of the iconography of scarlet macaws.

Tail Structure of Stylized Macaws: Iconography and Epigraphy

The tail structure of several mythical species of birds in Classic Maya art consists of a glyph-like shape, as a connector between the body and the long tail feathers.. I would need many more examples to know whether these “glyph cartouche” concepts are intended to be generic or whether each bird species has a slightly different feature. The other question is whether these glyph-like designs have a phonetic meaning, or not.

I have never dissected a macaw so I am not able (yet) to suggest whether this glyph-like design is a play on words, or whether an actual bird body structure has such an intermediate area.

In my PhD dissertation I noticed the stylized tail structure of the Principal Bird Deity (but remember, this is normally a snake eating hawk or falcon, not a macaw).

The Bird being shot by Hunahpu and Xbalanque

in most Maya art scenes is not a macaw

There are endless renditions of the Hero Twins, Hunahpu and Xbalanque, using a blowgun on an impressive bird deity at the top of a tree. The Popol Vuh clearly calls this bird 7 Macaw; and says the tree is a nance tree. But the nance tree is almost never shown in Maya murals or sculptures or vase paintings: the tree on which the sacred bird sits is normally a calabash tree. And most importantly, the Principal Bird Deity (the creature on top of the tree in almost all cases) is a snake eating falcon (Hellmuth 1987).

The only place a macaw is seen in Classic Maya art related to the Popol Vuh is at Copan; the giant macaw monster who even has the Hero Twin’s arm in his bird beak. But in 99% of all the many known instances, the Principal Bird Deity is either not specifically macaw-shaped, or is clearly shown associated with a snake in its mouth (suggesting it is a snake-eating falcon or hawk).

Macaws of Guatemala and Honduras definitely need more study

To photograph macaws close up, two good places are:

- AutoSafari Chapin, near the Pacific coast of Guatemala.

- Macaw Mountain, near Copan Ruinas, Honduras

To see tame macaws, but flying naturally (in other words, wild, but living within a park), the best place is

- Copan Ruinas park, Honduras

To see wild macaws, in their full natural habitat, a really good place to study scarlet macaws is

Las Guacamayas Research Station, Rio San Pedro Martyr, El Peten, Guatemala

First posted October 2014