Over twenty years ago Nicholas Hellmuth wrote what has become an oft-cited resource on pre-Columbian Maya utilization of local plants and animals in their daily life. This article, published by leading outlet for scholarly research, Academic Press, stands today as a reference to the difference between fact and theory. It is a theory that ancient Maya civilization was maintained by milpa cultivation, primarily of maize. It is a fact that the milpa system principally of maize was unlikely the economic foundation during the height of the Classic period in either Guatemala or Mexico. Entire dissertations have already been written on this subject, usually trying to stress one plant basis or another: Dennis Puleston proposed ramon; other articles featured root crops. And But the venerable early Mayanists such as J. Eric S. Thompson just talked about milpas and maize (though in his ethnographic research he did see and list dozens of other edible crop plants).

Like many other things in life, it turns out to be more practical not to go to one extreme or another. The agriculture of the Maya was diversified, and evolved over time. Slash-and-burn agriculture was theoretically practical in the low populations of the Preclassic and Post Classic, and is clearly the popular practice in the last several hundred years. But during the majority of the Classic period, it is more likely that diverse crops sustained the substantial populations of Tikal, Yaxha, Calakmul, Caracol, Palenque and comparable centers.

In the spirit of recognizing diversification, and in the reality that sensible land use today necessitates phasing out the destructive features of slash-and-burn agriculture, FLAAR is working on long-range projects to bring back the reality of diversified crops. One way to accomplish this is to produce a realistic inventory of the plants utilized by the ancient Maya and compare this with the utilization of crops used by the indigenous Maya today. Recently we worked together with the Asociation FLAAR Mesoamerica and SANK to initiate a practical project with immediate benefit to local communities of Mayan farmers, as well as simultaneously producing a reference archive for students and scholars all around the world who can’t easily afford to be on-site in the Mayan area.

SANK is a non-profit NGO (non-governmental organization) in Chisec, Alta Verapaz, that is working for the conservation of their cultural heritage and natural resources. Chisec is in the cultural border area from the piedmont of the Highlands that slope down into the Peten. The Mayan archaeological site of Cancuen is the nearest large Classic Maya site.

We prefer to work with local organizations in Guatemala for many reasons, primarily that this allows producing immediate positive benefits for the local communities. FLAAR is not the kind of international organization that swoops in, gathers materials, and then takes them all back to some distant foreign country. Indeed FLAAR is one of the organizations that maintains an actual presence within the country. Plus, we include Guatemalan scholars on our teams.

This project utilizes the local field experience of biologist Eduardo Sacayon, and advanced student in tropical ecology at Universidad San Carlos, Guatemala. He has undertaken botanical and zoological studies in this area during recent years. The project team includes Rodrigo Giron, a student at Universidad Landivar.

The other benefit of working with a local NGO, local foundations, and local associations, is that they already know the area. More importantly, they already have prioritized what will provide the best immediate benefits as well as long-term benefits to their communities.

The first field trip was to form an archive of digital photographs of reasonable quality so that SANK and their NGO partners such as Counterpart could have good quality images in their PowerPoint presentations of their ongoing projects. FLAAR donates these images to SANK. This NGO covered the cost of gasoline, hotel, and meals. FLAAR (USA) provided the expenses of rental car, covered the staff, and overhead operating costs. In the future we will seek to have these all field project costs covered by grants or the budgets of local organizations within Guatemala, but to get the project jump-started, FLAAR used its regular funds to get things moving.

Ethno-botany and Iconography.

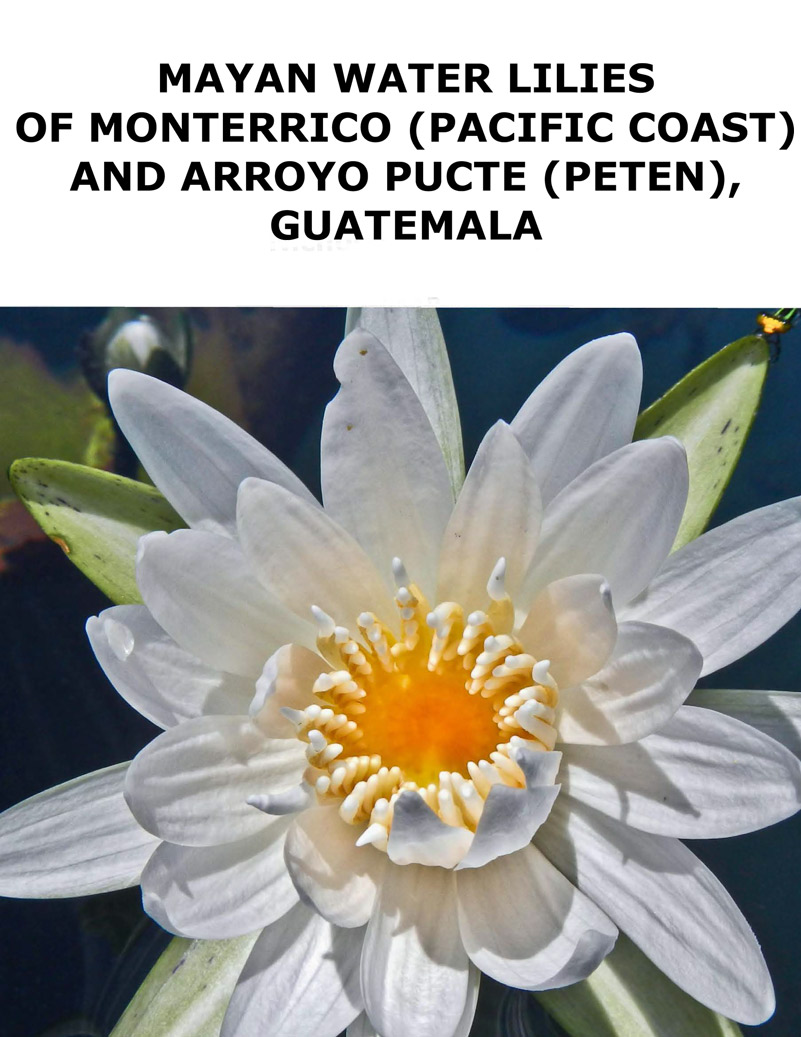

Since many plants and flowers are included in Mayan art, a major part of our long-range program in ethno-botany will be to identify the plants that are most common in Mayan art and to find these flowers in the rain forests and fields, so that a reference archive is available to show the actual species and then to reveal how the artist stylized the plant. FLAAR has already done this to some degree for the sacred water lily flower: the results are in “Monsters and Men in Maya Art,” the PhD dissertation of Dr Hellmuth.

Now that digital imaging technology is available, we intend to form a reference archive of water lily plants and flowers, as well as other flowers that can assist epigraphers and iconographers. For example, we now have completed another five seasons of field trips to both the Monterrico area and tributaries of the Rio de la Pasion area where water lilies abound (on tributaries of the Rio de la Pason; there are none on the actual river itself).

As a result of these annual field trips, presently FLAAR has the largest photo archive in the world on the white water lily of Guatemala.

We are also tracking down each and every flower which appears in the pre-Columbian art of Teotihuacan or the Maya.

For edible plants we have been focusing on fruit trees. At least 75 different edible fruits exist (the actual count depends on how you define “fruit” and whether you include fruits from vines or only from trees).

We have been accomplishing breakthrough research on flavorings for cacao. Plus we are advancing well on a long-range research program to learn about flavorings for cigars of the Classic Maya (and Aztecs). We are also making annotated lists of what leaves other than tobacco were smoked during prehispanic times.

Twice we have had exhibits of our high-res digital photographs at MOBOT, the Missouri Botanical Garden (in St Louis). Here we are also cooperating with botanist Charles Zidar. We are also in communication with Dr Suzanne Cook who is doing ethnobotanical research among the Lacandon Maya of Chiapas.

I estimate that overall we have over 50,000 high-res digital photographs of utilitarian plants of Guatemala, as well as sample photographs of pertinent utilitarian Maya plants of El Salvador and Honduras. We hope in the future at a botanical garden or university or foundation will be able to provide grant funds so we can turn over our entire photo archive to such an institution, as additional funding would make it possible to have this photo archive available to botanists, Mayanists (iconographers, epigraphers, ethnobotanists, archaeologists) and students around the world.

But in the meantime, we have launched our modest web site, www.maya-ethnobotany.org to show samples of the quality of our photography (photos by Nicholas Hellmuth and by Sofia Monzon).

Most recently updated April 26, 2013

First posted April 25, 2006.