pre-Columbian_Mesoamerican_Mayan_ethnobotany_Mayan

|

Ayote (Curcubita pepo) from the FLAAR Mayan ethno-botany project

|

This project is related to our decades-long interest in Mayan iconography as well as our continued interest in Mayan ethno-botany. Squash (ayote, calabaza, etc) is a major food crop for the Maya still today.

The sacred book of the Popol Vuh tells us that Hunahpu is decapitated by killer bats during a heroic tribulation one night. His head is replaced by a squash so that he can play in the ballgame the next day (in the translation by Recinos, re-translated into English by Morley, the head is listed as a turtle, but when it is hung above the ballcourt, and hit, then squash seeds spill out. Thus we interpret the head as a squash from the beginning, and that turtle may be an incorrect translation).

Further documentation of the relationship of squash plants with the ballcame comes from a likely representation of the squash vine with squash flowers on the ballcourt reliefs at Chichen Itza, Yucatan, Mexico. A squash-like vine comes out of the decapitated head of the Post Classic Maya ballcourt personage.

Vines are also depicted in the ballgame art of Post Classic Cotzumalhuapa. Whether these are squash or not is not often discussed.

Karl Taube reports that on the carved columns of the ballcourt at Chichen Itza, squash sprouts from the heads of the characters emerging from the double-headed carapace (the Maize God rises from the splitting top of the carapace).

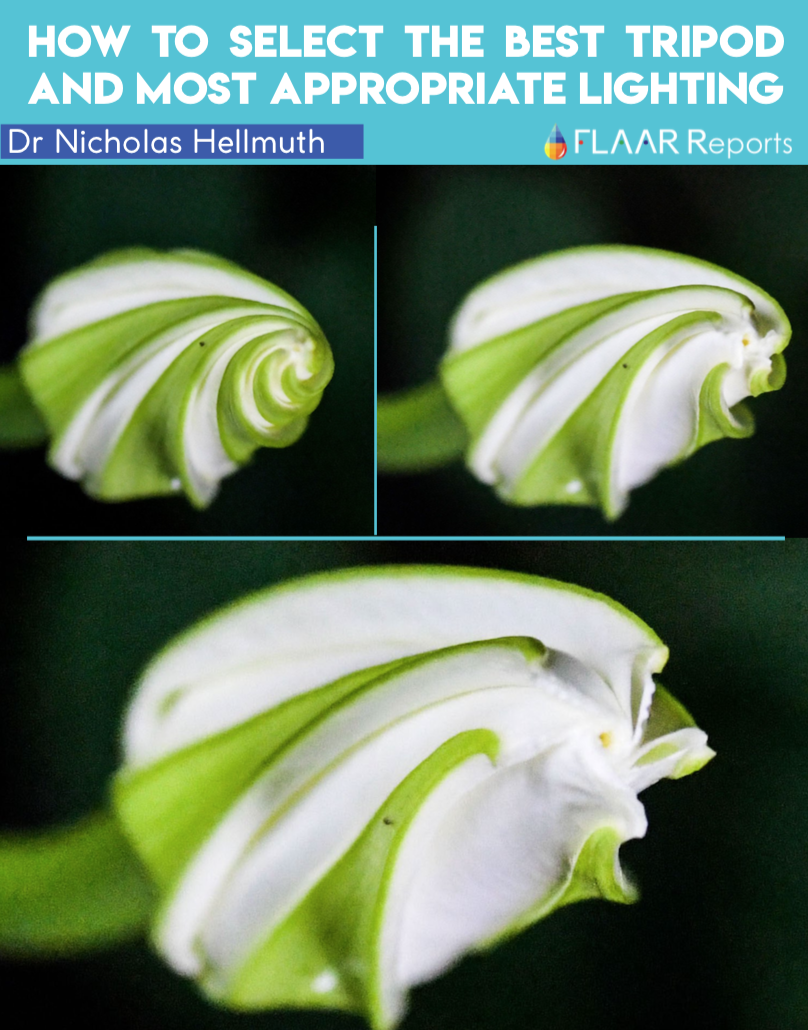

Botanical aspects and photographic quality

|

Maize (Zea mais)

|

|

Cacao plant (Theobroma cacao)

|

Most photographs which are available of plants and flowers are not taken with the needs of Mayan iconographers in mind. Sometimes the lighting and quality of the photographs simply is not adequate. Whereas our photos for a web site tend to be simple basic shots, our long range goal is to produce professional quality photographs of each major aspect of flora, fauna, and minerals of Guatemala so that iconographers can have better reference material.

Lighting, composition, and background (cluttered or not) are aspects that are a constant battle (also with us at FLAAR). So in the bottom two photos (taken in our own Mayan ethno-botany garden), the lighting is okay, but the background is a bit cluttered.

In order to obtain better photos of sacred Maya plants, we started our own Maya milpa at our office

The advantage of having the plants in our own garden are that we can learn about every aspect of the plants and flowers without constantly needing to make field trips out into the jungle.

Our first step was to plant several species of squash in our own garden. Since we are in a densely populated city, rather obviously we don’t have much space. But at least I wanted to see what a squash plant looked like. I quickly learned that they grow very very fast. Then I noticed that they have a distinctly characteristic placement of the leaves (alternating sides on the vine). We will continue to plant, grow, and harvest squash plants to gain a larger photographic archive.

Many species of squash exist. For our first experiment the idea was to get “a squash that was roughly the size and shape of a human head.” The ones we planted were of this general size and shape. If the ground were more fertile and if they had fertilizer they might grow a tad larger. A botanist can eventually make a list of appropriate species. Obviously what is sold in a supermarket today in Guatemala is not necessarily the same species that was raised in the Quiche highland area of 15 th century Guatemala. And since the myth of the Popol Vuh probably has its origins in the coastal lowlands, the species favored in the Quiche area may have been different from that of the lowlands in 1000 BC.

|

Here are Luis and Ximena in the FLAAR project garden with the ayote plants.

|

Rechecked August 24, 2009.

First posted July 25, 2007.

FLAAR is interested in all plants that appear in Maya murals, on ceramics, on sculpture, and are mentioned in the Popol Vuh. For example, a pertinent plant mentioned in the Popol Vuh is Tzite, palo de pito, Its red seeds are still used by the Quiche Maya for divination still today. We found this tree in the Mucbilha community fields and orchards (near Chisec, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala, far from Quiche territory). In fact it was a tree common in the area where they had recently placed vanilla vines.

We are also studying general utilitarian plants. We have a basic interest in medicinal plants but so much of that has already been studied, that we concentrate more on trees, vines, and thatch trees used in making the indigenous houses, for example, or plants that were crucial for diet, or plants for dye (dyeing food such as with achiote, or dying textiles such as with palo de tinto).

Also, practically every plant in the forest and fields had medicinal use for the Maya shamans and curers, so these thousands of species would require substantial grant funding and additional staff. So we prefer to be more realistic, and concentrate on plants such as agave, amate, balche, cacao, cashew, ceiba, copal, croton, flor de mayo (key flower for Lacandon maya), hule, jicaro and morro, nance, papaya, palo jiote, etc.

We are especially interested in cacao species

FLAAR has been studying pataxte for several years (after first seeing it perhaps a decade earlier at Takalik Abaj and of course reading about pataxte in the Popol Vuh decades before we found the actual trees).

During 2014 we went to many diverse eco-systems in Guatemala with this Theobroma bicolor.

Next we began to study Theobroma angustifolium. It took several weeks to find this and we had a thousand kilometer round trip drive to get to the cacao silvestri location.

If you wish a list of 96% of the utilitarian plants of the Maya, here is an unprecedented list: edible plants, edible leaves, edible flowers, edible roots. Plus plants for basketry, cordage, house construction. Maya spices, condiments, flavorings: all kinds of plants used by the Classic Maya, including sacred plants. |

and of Maya civilization |

at Copan Ruinas, Honduras, with permission IHAH. |

Caves related to Maya iconography and the Popol Vuh.

While in the area of Mucbilha to study vanilla, cacao, palo de pito, and achiote, we took advantages of the fact that the same village was the entrance to several substantial caves. Now that I have experienced the caves of Candelaria at Mucbilha, I notice how much I missed as an anthropologist and iconographer for not having visited them before.

The caves in Alta Verapaz are of such ethnographic and ethnohistorical importance, that university programs should have as a requirement for all students who intend to practice as field workers or instructors in Maya studies, that these students should be required to know the Popol Vuh inside out and should visit at least five major caves in this region, or caves in Belize or in Yucatan-Campeche-Quintana Roo area.

Even though the version of the Popol Vuh that we have today in book form is obviously from the Quiche highlands, the cave system that they discuss is equally obviously from Alta Verapaz.

Caves have been crucial in the iconography of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica since Olmec times.

Chisec area as major destination for eco-tourism.

I personally recommend, highly, that individuals and groups who are interested in eco-tourism, and learning about Maya culture should visit the Chisec area in general and the Mucbilha cave area in particular.

Everyone in the village was pleasant and helpful. The food was yummy, indeed the scrambled eggs with veggies was so good I tried to talk Silvia into giving me her portion (but it was so good she naturally ate it herself). The guide was knowledgeable and patient, especially since I kept asking the same questions: "how many caves are there?" He patiently answered, "about 150."

The guide was knowledgeable and patient, especially since I kept asking the same questions: "how many caves are there?" He patiently answered, "about 150."

|

Mucbilha Caves in Alta Verapaz

|

|

Mucbilha is about 30 minutes from Chisec which is about 2 hours from Coban, Alta Verapaz. The entire area is gorgeous scenery. Sayaxche and the Peten is another several hours further north on the same highway. Summer is a great time because everything is green from the rains (several times a week, but usually afternoons or evenings). Winter might also be a good time (cool, and not much rain). March, April, and early May are a bit dry and hot; but after the rains begin later in May the jungle turns bright green the temperature cools down a bit.

More FLAAR Research in the caves of Mucbilha, Chisec area, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala

During Spring 2009 a FLAAR team returned to the extensive cave system of the Mucbilha area, north of Chisec, off the highway from Coban (Alta Verapaz) towards Sayaxche (Peten). Since I was lecturing in Serbia, Croatia, and Bosnia, my brother, architect Daniel Hellmuth, took my place. He brought his son, Henry Hellmuth. Eduardo Sacayon and Jaime Leonardo from FLAAR Mesoamerica did the photography.

|

Inside of the caves in the Mucbilha area, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. If you wish to visit these caves, contact Ricardo Coc Choc at: reservasiqmuc@yahoo.es Phone number (502) 5771-8451

|

The photo albums on this recent Maya cave photography will be available as free downloads in full-color PDFs shortly. The report by Eduardo Sacayon documents how to do large-format digital infrared photographs (IR digital photography with a 48-megapixel tri-linear scanning Better Light digital camera).

There are many caves in this area. We recommend you visit the caves in the Mucbilha area; the road from the main highway goes to this village.

If you ever wish to hire any of the FLAAR Mesoamerica botanists or photographers to show you how to do all their amazing photography, simply contact us in Guatemala by e-mail, readerservice@flaar.org. We ask a flat fee and a tax-deductible donation to help support our research.

|

Inside of the caves in the Mucbilha area, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. Photograph by Jaime Leonardo, one of the photographers who works with FLAAR in Guatemala.

|

During 2014 we continued to explore caves (of Xibalba)

We explored more caves in 2014, mostly in Alta Verapaz, many in remote areas. We avoid caves when local people say there are Maya burials or archaeology artifacts; these should be studied by IDAEH. Our interest is because caves are of utility for local people to develop alternative tourism, to help provide jobs.

As a child I explored caves on our family farm in the Karst area of Missouri (Ozark Mountains). We have many caves there.

Most recently updated January 2, 2015.

Updated June 24, 2008 and August 18, 2009.

First posted August 1, 2007.

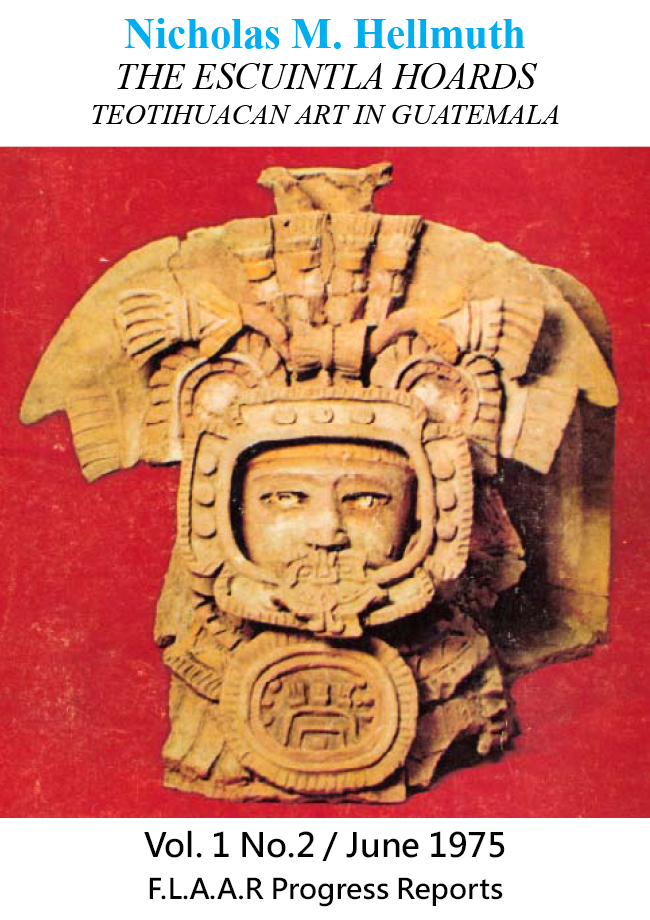

Tourists who visit Chichicastenango can see and smell the incense used by the Quiche Maya of today. The Lacandon Maya of Chiapas, Mexico have been burning incense in their Lacandon incense burners for centuries. Archaeologists find incensarios dating back over a thousand years. Indeed the symbol of FLAAR Mesoamerica is the lid of a Tiquisate region incense burner. Tiquisate is a culture based on local Costa Sur interpretations of Teotihuacan religious iconography introduced during the 3rd-5th centuries A.D.

But “pom” and “copal” are used in a confusing manner: these can be generic words, used for resin of various different trees. There are also several different species of Bursera which produce incense. Bursera simaruba is an even more common tree throughout Guatemala because it can grow in the deep rain forests or the dry desert-like areas as well. Tourists visiting Guatemala will see the gumbo limbo tree everywhere around the ruins of Tikal. However the gumbo limbo tree is not the copal tree, but both produce incense.

|

Copal Inciense, pom (Protium copal ), photographed by Alen Bubanja in Semuc Champey area.

|

Many other species of trees provide sweet-smelling resins that are also used in incense

The FLAAR Photographic Archive of Maya Ethnobotany is working on a long-range project to systematically photograph all the trees, processing, and final products of indigenous incense used in Maya religious ceremonies past and present. Copal pom is the best known and hence most obvious tree to start with first, but many other trees are involved. But we wanted to initiate our project with results both from studio photography as well as photography out in the field (Alta Verapaz region of tropical Guatemala).

Actually native rubber is also used in Mayan religious ceremonies. Unfortunately, 90% or more of the rubber plantations between Mazatenango and Takalik Abaj are Brazilian rubber, which is not native to Guatemala. But our team of botanists at FLAAR has located a few remaining places where indigenous Guatemalan rubber is still grown.

|

|

|

Harvesting copal pom Maya incense, El Portal, Semuc Champey, Alta Verapaz. Harvesting incense is done by women in this area |

Long range projects of FLAAR in Maya anthropology

FLAAR has a long range interest in Maya ethnobotany, especially in the utilization of sophisticated digital cameras and specialized software for producing photographs of flowers, plants, trees, fruits, vegetables, etc which are most politely described as better than average. If you check www.digital-photography.org you can see the kind of equipment that FLAAR has available.

Incense is the heart and soul of Maya religious ceremonialism, especially after the collapse of the Classic forms of ceremonialism which probably included considerable ingestion of fermented and mind-altering plant products. The Classic Maya took tasty plant byproducts in almost every orifice of their body except their ears. Although this shocks purists, just look at the Classic Maya funerary bowls and vases which repeatedly show injecting liquids into the body during ceremonies. Michael Coe of Yale University discovered this decades ago. Besides, virtually every other culture in the world, especially in tropical areas, imbibed or smoked about every tasty plant product they could get their hands on.

But our project is not on hallucinogens, definitely not on drugs, and not even on indigenous alcohol. The rate of intoxication on most college campuses on Thursday night, Friday night, and Saturday nights today is probably higher than that of the Classic Maya, so Maya practices a thousand years ago should not be surprising.

Our interest is on incense, and the causes and effects of incense in the culture and religious ceremonies. To understand the core relevance of incense in Maya ethnography, just read the Popol Vuh, or look at the artifacts uncovered in any archaeological site in Mesoamerica: incense burners are quite common.

Or simply visit Chichicastenango on Thursday or Sunday, and you will find incense all over the churches.

Our program is to document the complete cycle of planting, raising, harvesting, and processing the incense with professional quality digital photographs. This is a project of ethnobotany, not religious ecstasy. And primarily this is a photographic project: to locate and photograph the trees, to show how it is harvested, and to show how it is packaged and sold in the local markets.

FLAAR has also planted several incense trees in our experimental garden. The liguidambar is growing well, indeed this tree is a popular decorative tree in the Zone 15 area of Vista Hermosa II area of Guatemala City where our anthropology research offices are located.

|

Kinds of inciense used by the Mayas, photo taken by Mirtha Cano in FLAAR Mesoamerica studio.

|

Current status of ethnobotanical research on incense

You can find copal pom all over the place. You can find incense from pine resin throughout the Highlands of Guatemala (and adjacent Mexico and Honduras). But what is notable is that whereas almost every book that mentions indigenous Mayan incense talks about incense from palo de jiote, we have not yet found anywhere this incense is actually harvested or subsequently processed. Yet this is one of the more common trees throughout Guatemala. It even grows in the dry Rio Motagua area as well as in the adjacent Highlands and is also found in most parts of the humid Peten. There are beautiful specimens of palo de jiote at the Maya ruins of Tikal, Yaxha, and Seibal (Ceibal is how the ruins are spelled in Mayan language).

The situation is similar with liquid amber. This is one of the more common trees in the Highlands of Guatemala. Indeed where I live in Guatemala City the palo de estoreque is one of the most common trees planted along the streets near our research facilities (Zona 15, Vistahermosa II). I also have a healthy young liquidamber tree in my ethnobotanical garden alongside the house (right next to several palo de jiote trees).

Most articles and monographs that discuss liquid amber tree list it as an incense source. But I have yet to find where it is harvested and processed into incense. Ironically on the drive to several places in the Highlands this is the dominant tree species. But when you see people burning incense, they always say it is from copal tree or pine tree. Admitedly part of the problem is that copal and pom are generic words for incense (copal is not limited to define the specific copal tree).

Sooner or later we will find palo jiote and liquidamber being harvested, processed, and used as incense. We have a dozen other ethnobotanical projects going on simultaneously, especially cacao, pataxte, waterlily, ceiba, sacred flowers, squash (especially the flower and the vine) and several other projects. Our in-house full-time staff at FLAAR includes three experienced biologists of which two are primarily botanists.

Most recently updated August 24, 2009.

First posted January 2008.

When you ask about indigenous Maya incense, the usual answer is about copal incense, pom in local Mayan languages, Protium copal. But in reality there are at least six indigenous plants used to make incense for religious ceremonies of the Maya peoples of Guatemala:

- pom, copal incense Protium copal

- Palo jiote, muliche, indio desnudo, Bursera simaruba, gumbo limbo, chaca, palo mulatto, tourist tree

- Pine resin and pitch pine (ocote) as incense, Pinus pseudostrobus

- Liquidambar, arbol de estoraque, Liquidambar styraciflua

- Crotan sanguifluus (Popol Vuh), Croton (cochinal croton) red tree sap

- Rubber, hule, Castilla elastica

|

|

|

Ensarte incense from the pine tree or copal tree, purchased in the market at Solola, Guatemala. Photo for the FLAAR Photo Archive by Alen Bubana, University of Ljubljana, a volunteer working at FLAAR over the Christmas holidays.

|

So gradually FLAAR is initiating botanical studies and professional photography of these plants. Presently liquidambar and hule are planted in our Maya ethnobotany garden at the FLAAR Mesoamerica headquarters in Guatemala City . We intend to have all the species planted and growing during 2008. We also do field research all over Guatemala whenever we can find areas where these species grow. Actually liquidambar is a common decorative tree in Vista Hermosa: there are many of these trees growing within a few blocks of our offices.

So far finding the croton tree has not been easy. Other than croton being the most vivid use of a sacred plant in the Popol Vuh, I have not found coton mentioned much elsewhere, for example, we have not yet noticed plant products of croton being sold in local Maya markets.

Palo jiote is very common all over Guatemala: both in the Highlands, Lowlands, and dry desert areas too. Copal trees are found both in the Highlands and Peten lowlands, but are most common in Verapaz, growing well in precisely the same areas where cacao and achiote also grow. This incense is also, so far, not common in markets (if it is present, we have missed it; the markets are filled with copal and pine incense, and liquid amber (sweet gum, not pertified amber from pine trees) are all common incense in markets).

Rubber is grown commercially in areas of the Costa Sur, but until we do more botanical studies, I can’t be sure whether it’s a South American or recent commercialized hybrid that is grown today. I am interested in the original pre-Hispanic species.

Although our background is in archaeology of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica since the 1960’s, our present projects are more in the ethnographic and ethnohistory aspects of anthropology, using advanced digital photography so that our projects stand out as unique. With better digital images it is easier to produce articles that are interesting for people to read.

|

|

|

|

Incense Ensarte de Chuchito, |

|

|

Incense round shape is used primarily for pine incense, photo by Alen Bubanja.

|

|

Copal Pom in Ensarte de Chuchito wrapper (Protium copal) , photo by Alen Bubanja.

|

|

Another forms of Inciense bark from Liquidambar styraciflua, Cupressus sp., Quercus sp, etc. that you can find in local markets in Guatemala. photos by Alen Bubanja.

|

Incense from pine is by far the most common for Maya.

In the markets of Highland Guatemala, especially Momostenango and Quetzaltenango, pine is by far the most common incense for indigenous Maya usage. Pine burned as wood (ocote, pitch pine in English) as well as in several sizes of incense balls. In some cases the bark of the local oak tree is used to wrap the pine incense. Since oak trees have many potential uses themselves, a further ethnobotanical and ethnographic study needs to be made to determine the role of oak products in Maya rituals, especially in the Highlands.

Much of the information on Maya incense on the Internet is confused due to misunderstanding due to mistranslation.

Because so many words have double meanings either in Spanish or Mayan, there is a lot of misinformation on web pages.The words incense, pom, and copal are the most frequently misunderstood.

We need to undertake further studies to understand the meaning of "ambar" because in English this means solidified resin of a pine tree. But if a Maya says they are burning "ambar" this may be sweet gum, estoraque, and not pine amber.

Most recently updated June 24, 2008.

First posted January 2008.

Cacao is a major food crop for Guatemalan people today; cacao was a major food crop for indigenous Maya people a thousand years ago also. Cacao got stuck with the modern name cocoa so cocoa powder is what is sold in supermarkets in the USA by Hersheys and all the other brands. But the proper original name is cacao.

Although there are some areas of Guatemala where cacao is common, it can be grown almost anywhere that you provide some shade and enough moisture. I originally had about eight plants outside in my garden and about the same number inside my house at an elevation of about 1300 meters in chilly Guatemala City. However in two years the tallest and most robust of my seedlings is still only about 1 meter tall, and most are less than that. A few are only 40 cm tall, and that is after two years. You quickly learn that some areas of the garden the plants grow slowing; ones in pots in deep shade most of the day grew the best so far. But we learned that they did not like to be transplanted from the pot to the garden soil.

Now, three years later (so the plants are over 5 years old), the tallest of my cacao “trees” is still bush-sized, at less than 3 meters. But being in the middle of the city, and with lots of tall trees, plus the shade of a 6-level house, the cacao plants don’t get quite enough sun. Due to the colder weather at this altitude, they only bloom about once every two or three years. And the winds and rain usually knock off the flowers before they can turn into pods. But one year we did get pods (despite the unlikely presence of the midges which are normally expected to pollinate cacao; I doubt if these midges are common in the middle of a city where I have about the only cacao for several kilometers around).

|

Pataxte fruit pod, Theobroma bicolor

|

There is a Theobroma cacao tree inside the museum of Copan Ruinas village, Honduras, that flowers and somehow even fruits (how the flowers of a single tree are fertilized I will have to leave to a botanist).

In the last several years pre-Columbian Maya cacao has become a popular topic, after all, most of us buy cocoa in the supermarket and drink milk chocolate and enjoy chocolate candy. Hundreds of books exist on chocolate and many ethnobotanical monographs on cacao and chocolate have been published in the last few years. We list some of the better books and articles in our bibliography on cacao, cocoa, and chocolate.

Cacao in Maya archaeology: cacao seeds in Tikal Burial 196.

My first encounter with Maya cacao was in 1965, at Tikal. At age 19, while a student at Harvard, working at Tikal twelve months for the University of Pennsylvania, I discovered a polychrome painted Maya vessel filled with food remains. The pot was about half filled with crusted remains of food; in the crust were the hollow shapes of what had once been a bean-like seed.

Since this was in 1965, and today it is over half a century later, I don’t exactly have my field notes handy. But at age 19 I naively assumed these were frijoles (beans) in the pot. As I look back in my memory, I now question whether the “beans” were probably cacao. To tell for sure would require finding the University of Pennsylvania records.

This tomb is known popularly as the Tomb of the Jade Jaguar.

I am still studying Maya cacao (and jaguars) after all these decades.

|

This is a young growing cacao plant we had at the FLAAR office.

|

During the years that FLAAR organized educational field trips (1970’s-early 1990’s) to help interested people learn about Maya culture, we often came into contact with cacao trees in the area of the Rio de la Pasion and Rio Usumacinta. But the major areas for cacao plantations are in Alta Verapaz area and across the other side of the mountains, in the piedmont area between the Mexican border of Chiapas and Escuintla. Chocola and Takalik Abaj are two out of hundreds of fincas where you can easily find cacao groves today in the piedmont area.

Although Soconusco (Chiapas, but directly on the border with the same eco-system of Guatemala) and Tabasco (Mexico) are the areas of cacao production which are mentioned in most books and articles, we have found other areas of cacao production in Guatemala which do not seem to be known to the authors of peer-reviewed journals and books published by universities. This is the difference between writing books on chocolate at your university, and writing about chocolate living in Guatemala and being able to get to know remote areas of this actually rather large country.

Since there are already many ethnobotanists, archaeologists, and iconographers already studying cacao, where FLAAR can also assist to provide something special, namely to utilize our experience with advanced digital photography to obtain better than average photographic records of cacao. We then test and evaluate different kinds of wide-format inkjet printers to print large-sized photographs. This kind of photograph can be used in museums or for general photo exhibits.

|

|

Achiote (Annatto) and vanilla are sometimes grown in the same areas as cacao.

Achiote, Bixa orellana, annatto, is a major food crop of the Alta Verapaz region of Guatemala. Most of the same villages that have cacao orchards in the house lots also have achiote. This is because the ancient Maya used achiote powder to dye their cacao red. I have noticed two different kinds of achiote: that grown in Chisec area of Alta Verapaz and that nearer the ruins of Cancuen.

I have also found vanilla plants in some of the village orchards of Alta Verapaz. Although vanilla is best known from the El Tajin area of Veracruz, Mexico, and Tabasco, you can find vanilla being grown in many lowland areas of Guatemala and also in higher elevations of Alta Verapaz.

Cacao as a sacred drink for ritual use among the ancient Maya.

Many pre-Columbian polychrome Maya vases have hieroglyphic inscriptions that indicate these fired clay pots were used to hold cacao drink. The importance of cacao as a special drink is emphasized by the presence of actual clay effigy containers in the size and shape of a cacao pod. I thank the La Ruta Maya Foundation for facilitating our photography of three such cacao vessels (we show one here). We are preparing a longer and more detailed report on cacao, as well as on the digital camera and lighting equipment used in this photography.

Cacao flavoring of the pre-Columbian Maya and Aztecs.

In recent correspondence with Michael Coe, he suggested that since FLAAR has botanists in-house on staff resident in Guatemala, that we should gather more local information on the different Post Classic Aztec and Maya flavorings for cacao. So I began this long-range ethnobotany project in late 2008. Today, in late 2014, we are well advanced in knowledge of the diverse plants which were mixed with cacao a thousand years ago.

Diverse species of cacao other than Theobroma cacao.

Cacao pods (pochas in local Guatemalan Spanish) come in every imaginable size, color, and shape: fat, thin, long, knobby, smooth; green, yellow, red, orange. Pods of pataxte, Theobroma bicolor, have a distinctive pattern, especially when the pod is dried out. Yet I have seen the identical pattern on fresh pods in Alta Verapaz on a tree that I am sure is Theobroma cacao.

My interest in size, shape, and color of the pods is because most archaeological, iconographic, and epigraphic discussions of cacao simply talk about cacao or chocolate. This is precisely how I spoke about this tree, fruit and drink for decades: until I was face to face with my first pataxte tree (at Takalik Abaj archaeological park many years ago). This was as different from a “cacao” tree as night is from day or winter is from spring. So that summer I began to learn about pataxte and the next year it was possible to find several pataxte trees near where one of the FLAAR photography assistants grew up, in an area near the Mexican border. There will be articles and discussions about the ethnobotany of pataxte in FLAAR Reports upcoming for the next several years as we assemble a world-class photo archive of cacao.

This interest in size and shape of the pods is of additional importance to archaeologists and botanists because the pods on pre-Columbian effigy vessels clearly are depicting different species or at least sub-species of cacao. But these differences are seldom, if ever, identified in the captions. Indeed I am not convinced that all botanists would accept all the pods on pre-Columbian effigy containers to really be cacao anyway. There are several other fruits that are the same size and shape as a cacao pod (but true, not all of these fruit from the trunk as does Theobroma cacao). I gave a lecture to anthropology students and faculty at Tulane University a few years ago about all the native pods in Guatemala which are of similar size and ridged shape as cacao and pataxte pods.

I pointed out to the botanists working at FLAAR that it is safest to be neutral about identifying any “pod” in Maya art as Theobroma cacao until it is clear that the pod is an acceptable size and shape for common cacao.

About a month later Mirtha Cano sent me a JPEG that illustrated cacao de ardilla (cacao of squirrels) Herrania purpurea (Pittier) R.E. Schult. This same cacao is known (in Costa Rica) as cacao de mico and cacao de Monte (the Malvaceae.info web site index). But so far we have not found this cacao species in Guatemala, though we are looking.

The point is that cacao is not just one fruit, it is a diverse range of fruits and trees with different sizes and shapes and decorations on the pods.

We list some of the better books and articles in our bibliography on cacao, cocoa, and chocolate.

Most recently updated September 9, 2014.

First posted June 25, 2008. Updated January 26, 2009. More photographs added May 25, 2010.

I saw my first ceiba trees in Guatemala in 1965 (as a Harvard student, working for 12 months for the Tikal archaeological project of the University of Pennsylvania museum). I was growing ceiba trees by the early 1970’s (along the entrance to my Yaxha Project camp, El Peten, while working five years to create the national park there). I continued studying Ceiba pentandra trees in the 1990’s and have increased my research on the conical spines over the last eight years. Today in 2015 I am still studying these trees: especially in the Costa Sur, Alta Verapaz, Izabal, and El Peten.

Thus it is sad to see how many web sites copy-and-paste mistaken beliefs about the Ceiba trees. Our page here is to correct a few misconceptions.

“Largely branchless” is a copy-and-paste error from people who have perhaps only seen the famous Ceiba pentandra tree of Tikal

80% of the web sites simply copy-and-paste (mis-)information from other web sites who have copied and pasted from elsewhere. To call a Ceiba pentandra tree “largely branchless” is no surprise, since 80% of the trees that grow along the tourist route have not many low branches.

But there are plenty of giant ceiba trees which have branches all up and down the truck. This is often a result of the top of the tree being injured (by lightening) so all the energy of growth remains in the lower area of the tree trunk.

If your data base is 100 ceiba trees, instead of one or two, it is easier to understand the growth patterns of Ceiba pentandra. Yes, most really tall trees have no branches, since the lower areas are in shade (caused by surrounding trees). When you see tall Ceiba trees with no branches in the middle of a cane sugar plantation, there are no branches because most were chopped off, or, this tree is 300 years old and 200 years ago it was still a jungle around it. The cane sugar clear-cutting only happened a few decades ago.

But if a ceiba tree has no other trees around it, and lots of sun everywhere, it may indeed have branches everywhere (especially if the top of the tree is injured, but I estimate this upper tree injury is not absolutely required to encourage branches all up and down the trunk).

Sacred ceiba tree of life, the world tree of Maya religion and cosmology

Most civilizations of Mesoamerica show the spiny ceiba tree in their art: Mixtec, Aztec, Maya and other cultures. In most contexts it is clearly a sacred tree. There are plenty of ethnohistorical references to the ceiba tree as a giant tree upholding the world.

The roots are considered to go down into the underworld, but frankly most of the Maya area is Karst and there is not much soil, so the roots go horizontally along the surface of the ground, not way down. But in other non-karst areas the roots probably go down deep.

Spines (conical thorns) on the trunk of young ceiba trees are a major motif in Maya art

Incense burners from Lake Atitlan (Highland Guatemala) as well as funerary urns from the Quiche Highlands, and incense burners and cache vessels from Lowland Maya areas, frequently have effigies of sacred ceiba tree spikes up and down their sides. It is well known to all iconographers and most archaeologists that these spikes mimic the thorns on the trunk of young ceiba trees.

I am currently beginning a collection of ceiba bonsai, and already two totally different species of trees have been brought to me as “ceiba.” One had five leaves and obvious spines that were what I expected of the sacred ceiba of the Maya. The other “ceiba” had the swollen trunk that is also a typical feature of many of this family; but this other “ceiba” had seven leaves (and no spines, at least not yet).

Botanically the spikes are called stem emergences.

Botanists also tend to call these prickles. Sorry, but it is more realistic to call them conical spines or conical thorns.

Spanish nomenclature is very lax, such as for “zapotes,” as an example. Many completely different fruits are called zapote. For ceiba, the overall family is large, and many trees share some of the basic characteristics. But the tree that is generally considered the Maya tree of life and the national tree of Guatemala is Ceiba pentandra. It is called the kapok tree in English but almost all visitors of whatever language quickly learn to call it a ceiba.

Because the lay-person terms are so imprecise, and because even botanical names get changed, this is why FLAAR is establishing a photographic archive of all the plants, trees, flowers, fruits, etc that were sacred to the ancient Maya. I am primarily interested in species that appear in Maya murals or ceramics, or fruits which were shown as effigy vessels: cacao and guicoy are two of the most common.

More than one species of ceiba has spines: Two major species of ceiba in Guatemala

Eduardo Sacayon has pointed out to me that there are two major species of Ceiba in Guatemala; Ceiba pentandra and Ceiba aesculifolia (Pochote). The one I know best is the sacred tree of the Maya and the national tree of Guatemala, namely Ceiba pentandra.

Hura crepitans is named the “sandbox tree” in the Virgin Islands (St John, Virgin Islands, Beach Guide). But to me some of the images on Google of this tree looks like a perfect example of the Ceiba aesculifolia. Since just the trunk full of conical spines is pictured, only a botanist can tell for sure, and they normally need to see the flower. None of the Hura species that we have found in Guatemala have many spines; most Hura in Guatemala have no spines.

But there are several other trees in Guatemala that do have lots of conical spines. One is the genus of Zanthoxylum species. There will be many FLAAR Reports on “spiny trees” in future years.

COPNA, Erythrina fusca, also has spines. The reason we spend so much time on finding all the trees with spines is because Peten area Maya incensarios, some cache vessels, many later Quiche urns, and even Early Classic Teotihuacan-related Tiquisate area rectangular funerary ceramic boxes have the same conical spines (in clay). So it is suggested that iconographers cite this FLAAR web site as well as the FLAAR Reports that introduce iconographers to the actual flora and fauna that the Maya saw around them. Most of what is presented in Maya paintings and sculpture is a reflection of their natural world, from caves to specific flowers.

Not all Ceiba pentandra trees have prominent spines

Every tree species has variations. In many cases the spines simply do not exist. There is a substantial stand of Ceiba aesculifolia trees along the Rio Motagua. We have been doing photography here many times in the last five years. Most of the trees have spines, but many simply do not have spines, and not because someone has chiseled them off the trunk.

30 km away, we found a Ceiba aesculifolia with the longest spines I have yet measured, 5 cm for the longest spines on this remarkable specimen. Of course most ceiba trees, both species, have spines only one or two centimeters long; 3 cm at most (for an average tree; there are exceptions).

In other trees the lack of spines on the main truck is because they are old; so there are no more spines on the truck. But often you can see spines on the fresh young branches way up in the tree. In other instances the spines on the trunk have been knocked off so people do not scratch themselves.

If you were to photograph 20 trees with spines (as we have) there are not more than one or two that have the same pattern or size or shape of spines. I recently photographed a tree (perhaps 20 to 40 years old) that had several brown spines (but not ones that looked brown because they were sick or dying).

FLAAR Research in Maya ethnobotany, especially related to Maya iconography

| Nicholas Hellmuth showing the ceiba tree the day it was planted in the garden of FLAAR offices. |

As a comment, there are actually several other species of trees in Guatemala that also have similar spines: one of these trees has spines that are close to the same size and shape as those of the ceiba. We believe that the Maya potters and priests are imitating the spine of the Ceiba pentandra, but the other species need to be checked also, and at least added as a footnote.

|

|

|

The trunk of a young ceiba tree planted in FLAAR's garden

|

There is a similar issue with identifying the “tree of Hun Hunaphu’s head” as a cacao, when the Popol Vuh clearly states it was a calabash tree (moro in local Spanish). There are actually two other trees (in addition to the cacao) which bear fruit from the trunk: the papaya and the jicara.

The jicara is a close relative of the moro. The moro is plentiful in the Departmentos of Zacapa and Chichimula; the jicara is reported to be common around Salama. Or at least this is where the artisans live that make handicrafts from the jicara. Both these trees also survive in the Peten, where you find them in gardens of local inhabitants. We have also been told that at least one of these species is common in the Costa Sur area of Guatemala.

Over and over again, statements made in books on iconography copy earlier claims. J. Eric S. Thompson claimed the Sun glyph was based on the Plumeria flower (flor de mayo). This is absurd, and probably the mistake of Thompson which more epigraphers and iconographers have repeated for decades. We have been studying Plumeria trees and flowers and, sorry, they are not the model for the sun glyph.

I have found plenty of flowers with four petals that are models for the Kin glyph: none of them are Plumeria. We even raise these 4-petaled flowers (and Plumeria) in our Mayan ethnobotanical garden around our office. My interest in 4-petaled flowers started in 1965 since the Tomb of the Jade Jaguar (Burial 196, Tikal) had several bowls and vases with 4-petaled flowers on them. Between 1965 and last year, no one that I know of had identified these flowers. Now we raise them in our garden.

FLAAR Photo Archive of Maya Ethnobotany

FLAAR is currently working on creating a photographic archive of Maya ethnobotany, especially plants, trees, and flowers that are pictured in Mayan art of the Classic Maya. Since the ceiba tree flowers only occasionally, and during the months when it’s quite hot, it is a challenge to achieve good photographs of the flowers. And since most Ceiba trees are taller than a multi-story building, it’s not easy to get close enough to their flowers to photograph them.

By irony of fate, I found a ceiba tree blooming outside my hotel during a business trip to Israel (I am a consultant to many international companies that develop and manufacture UV-cured wide-format inkjet printers). Although this was probably an African species, the trunk was identical (to me as a non-botanist) in every way, shape, and form to ceiba trees I so frequently see in Guatemala.

Since our funding is limited, we tend to be able to launch field trips primarily during December-early January, and during May-August (the times of the year I am in Guatemala). But from 2008 onward we will do our best to have some photography field trips when selected sacred flowers are blooming. Our goal is to become a preferred source of absolute top quality images of pertinent Maya plants, flowers, fruits, etc. for botanists, ethnobotanists, iconographers, epigraphers, students, authors of books and articles on these subjects, and members of the interested public.

Tzite (Palo de Pito), moro, jicaro, and Sangre de dragon (croton) are trees we also intend to study: trees that are mentioned in the Popol Vuh, trees that are sacred, and trees that produce resin for incense.

Is bark of ceiba tree an aphrodisiac ?

A web site, nationmaster, suggests an ethnomedical use of a decoction of bark of Ceiba pentandra is an aphrodisiac. Sorry, 75% of the plants and fruits claimed to be aphrodisiac are not (tomato is the best example). Aphrodisiac chemicals do exist in plants, and these plants do grow in Guatemala, but I doubt the Ceiba is one of them.

X-tabay (demon) lives in a ceiba tree

David Bolles, a linquist of Yucateco Maya, notes that xtabay: demonio maligno que, en forma de mujer, vive en el tronco de la ceiba (Ceiba pentandra). We have found fascinating documentation on the insides of 300 year old Ceiba pentandra trees and are making lists of all the zoological species which live inside Ceiba trees.

Relationship between bats and ceiba trees

A Guatemalan specialist in bats, Universidad de San Carlos, has observed that the false vampire may inhabit hollowed areas of large ceiba trees (areas that have rotted and for whatever reason are now hollow inside the otherwise living tree). He said that some of these hollow areas are large enough for a person to crawl into and stand up inside (remember that a ceiba is one of the largest trees in the Central American forest and may live several hundred years; so there is plenty of space to have a small “cave” inside that bats like to inhabit. He said there was such a hollow Ceiba in the yard of Dos Lagunas field station.

Botanical and zoological articles indicate that bats pollinate Ceiba pentandra (Gribel etai, 1999). Surely the Classic Maya would have noticed a bat as large as the false vampire coming in and out of an entrance. And clearly the Maya would have seen the bats swarming around the pretty flowers (especially since the tree has no leaves when it flowers).

We have found and photographed six enormous Ceiba pentandra trees with caves inside the trees. As soon as funding is available, we now have enough photographs from the last eight years to produce a coffee-table book to help provide visual documentation on the Ceiba tree. We have taught ourselves a lot in recent years, even by planting the seeds from the kapok puffs and growing baby ceiba trees.

Most recently updated September 28, 2015.

Checked May 25, 2010. More pictures posted June, 2010.

First posted January 2008. Updated December 2008 and August 2009.

It is well known that the pre-Columbian Maya colored their cacao beverage bright red with dye from the achiote seed pod. I would call it more a food colorant rather than a flavoring.

Achiote (Bixa orellana), annotto or annatto in Maya ethnobotany.

Achiote (Bixa orellana) is a common bush or shrub around houses throughout Verapaz and Peten areas of Guatemala, especially in Alta Verapaz. I have noticed two kinds of achiote: a less common kind grown between Raxruja and La Union, en route to the Maya ruins of Cancuen, and the more common kind around Chisec, Alta Verapaz (on the highway from Coban to Sayaxche, Peten). Ethnohistorical records document that achiote was grown in these same regions when the Spanish first entered these areas.

|

|

My personal interest in achiote is because I have seen it for so many years as I drive along the highways and roads of rural Guatemala. Plus in the years that I did ethnohistorical research in the Archivo General de Indias (Sevilla, Spain) and Archivo General de Central America (Guatemala City), I noticed frequent references to achiote, especially when reading about villages in the Verapaz area.

And since I have been studying cacao, achiote is a natural extension, since achiote and cacao are often grown in the same fields. The Spanish conquerors commented that the Maya flavored and colored their cacao drink with achiote: red cacao drink!

I have seen the English word for achiote spelled and misspelled various ways:

Annoto, annotto, annato, annatto.

|

|

Red colorant in pre-Columbian times was also derived from cochinal and logwood.

The prehispanic Maya had three sources of red colorants from natural sources.

- Achiote, annatto, Bixa orellana

- Logwood, Palo de Campeche

- Cochinal, from an insect that lives on cactus plants

Plus of course many other colorants. I list above only the three most common and the three from plant sources. There are also many other plants that give dye of diverse colors and more than three plants that give red.

Be careful with claims that the red color of the Maya temples and palaces came from plants. Merle Green Robertson's evidence at Palenque (Chiapas, Mexico) suggests that the red color of most Maya building exteriors came from clays or minerals. Howver the color "Maya blue" seems to be a mixture of plant dye (indigo) and mineral or clay pigment.

FLAAR Photo Archive of Maya Ethnobotany

As time and funding become available more photographic coverage of achiote will be added to the FLAAR Photo Archive of Maya Ethnobotany. Presently this archive is primarily devoted to photographing cacao, water lily plants (especially flowers, seed pods, pads) and ceiba (especially the flowers and spines), so the photographs available on achiote so far we consider just snapshots, not formal studio-type photography of the kind that we accomplish with cacao.

I took some seeds of cacao and seeds of achiote from Mucbilha, Alta Verapaz. The cacao sprouted rather easily, but not a single one of the achiote seeds sprouted, even though the farmer kindly gave me seeds from his own seed bank. So we have a dozen young cacao trees now growing in the FLAAR research garden in Guatemala City, but not yet any achiote.

|

|

If you wish to join Dr Hellmuth on a Maya ethno-botany field trip, and learn about tropical botany, Maya culture, and digital photography of flowers and nature, you can offer a financial contribution towards a portion of the project costs, plus cover your expenses during the field trip. Field trips can be a long weekend, a week, or 10 days. Please communicate by Skype flaar_mesoamerica or telephone (dial as for a USA number in Ohio) 1 419-823-9218 (our offices are in Guatemala and St Louis but we still use our Ohio numbers).

|

|

||

|

Here are the different species of achiote.

|

||

If you are a student and wish to do thesis or dissertation work on Maya ethno-botany, or if you are a botanist or zoologist in any country, you are welcome to communicate with FLAAR by Skype flaar_mesoamerica. Our field office in Guatemala has two full-time bi-lingual biologists on staff plus the FLAAR Photo Archive of Maya Ethnobotany has an increasing number of professional quality photographs of plants and reptiles.

FLAAR is not a source of funding per se, rather we are a source of assistance and cooperation, with decades of field work experience in all ecological zones of Guatemala. You may wish to have one of our botanists assist you on your field trip. There is no fee for scholarly research under most conditions, though we do ask that you cover the normal day wage, local transportation, hotel and meals of any FLAAR biologists that you utilize while out on a field trip. If there would be shared joint publications resulting from this project, then the cost of the labor (day wage) will be refunded to you by FLAAR. Day wages in Guatemala are reasonable even with working on weekends or nights if necessary.

|

The Achiote was used by the mayan culture for red dye coloring and flavoring of cacao beverage. |

FLAAR also has 22-megapixel medium format digital cameras potentially available, for both studio photography of specimens as well as photography out on location. We have Nikon D300 and Canon EOS 5D plus a 48-megapixel large-format BetterLight (as well as professional quality reprographic stands for scanning specimens at high resolution). Our in-house Guatemalan staff has ample experience in operating these cameras, in our studio or out in the field (all are portable). It costs a lot less to rent these camera systems with a capable Guatemalan operator (who is also a biologist) then trying to bring comparable camera equipment from your home country and dragging it out into the field. Cost for this equipment requires insurance (a binder on your policy) and security (which we can provide) in addition to a nominal use-fee.

Photos added April 25, 2024.

First posted January 2008.

Updated January 5, 2009.

Edited August 24, 2009.

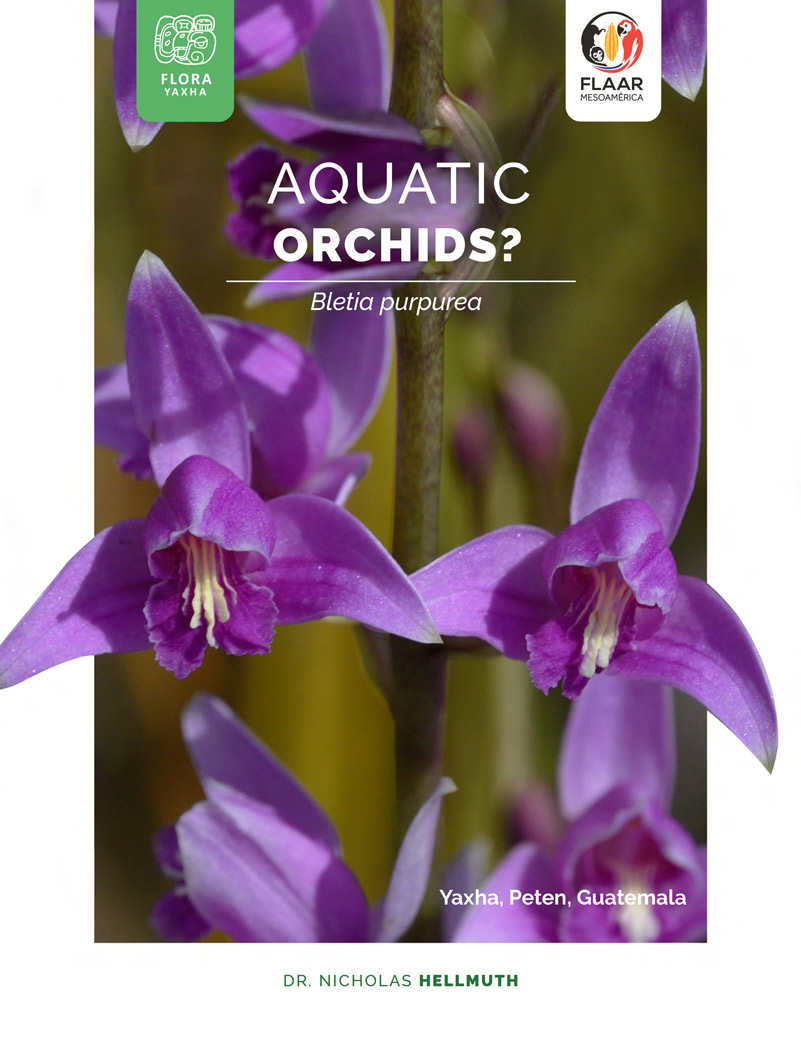

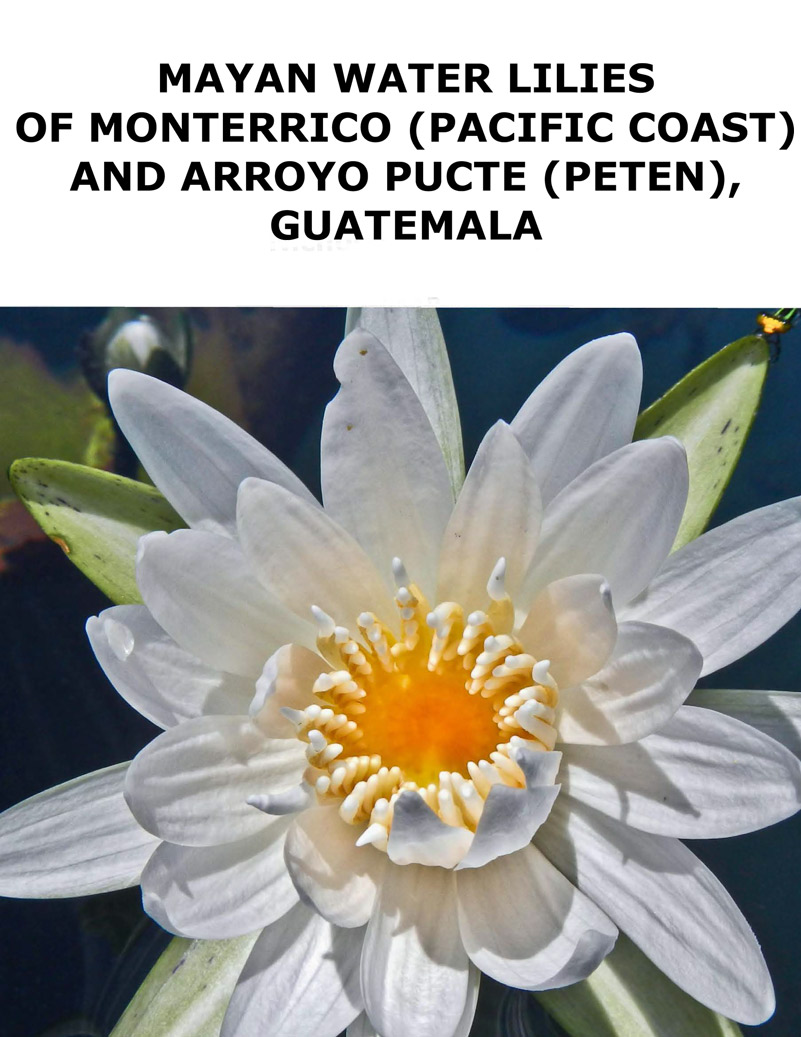

The water lily is pictured so often in Mayan art that it is clearly one of the top two or three most frequently rendered flowers during the Classic period of Peten. Stelae, altars, murals, and painted ceramics (vases, bowls, and plates) show water lily flowers.

This web page is not the place to question what part was eaten, smoked, ingested, or administered in an enema, but various parts of the plant are definitely edible. The Guatemalan biologist who was on the field trip (December 2007) ate parts of the plant because they had such a nice fruity smell. There were no adverse affects (though we would never recommend officially eating any unusual tropical plant; we don’t want to be responsible if the food disagrees with your system).

|

Nicholas Hellmuth taking underwater pictures at Peten.

|

Others in Peten say that there is a definite mild hallucinogenic effect if other parts of the waterlily flower are smoked. However our purpose is not to research drugs; the project is exclusively dedicated to testing digital photography equipment and ethnobotanical research on plants of utilitarian or food use in Maya agriculture of pre-Hispanic times.

|

Under water pictures of water lily flower taken at Peten.

|

“Nape” is what the water lily, Nymphaea ampla, is called by local people in Peten.

Normally people call the flower “nympha”. In my Spanglish I tend to call it “lirio de agua” (I have no idea if this is a real word). But in December I noticed that Don Ernesto was calling the plants or flowers “nape.” Since in English this means “nape of the neck” I was unable to get a Spanish or Mayan translation on the Internet easily, since searches turn up the meaning of neck for a thousand pages. As soon as we get a “translation” of nape as a Spanish or Mayan word for water lily we will update this page.

|

Here is Nicholas Hellmuth photographing water lily flower. Nicholas uses aPhase One P 25+ medium format digital camera back on a Hasselblad ELX camera with Zeiss lenses.

|

|

|

Here is a water lily area alongside the Rio San Pedro, downstream from Las Guacamayas Biological Station. But the massive areas of thousands of water lilies on this river is an hour downstream from Naranjo (about four hours from Las Guacamayas in boat).

|

FLAAR Photo Archive of Maya Ethnobotany.

The first two field trips we used only a Nikon D200 and Canon EOS 5D. The 22-megapixel Phase One P25+ was brand new, literally, had just arrived from Denmark and I had not used it yet. So it was utilized later, but not while we were in the canoe or out in the muck. Now, in 2015, we are using a 35 megapixel Nikon D810.

Because the water lily flower is bright white, it is always over-exposed in 90% of the photographs that exist. The pads, water, and especially the seed pods tend to be dark, so they are sometimes underexposed in comparison. We are working out digital methods to compensate by using HDR techniques (High Dynamic range). This will be explained in the FLAAR Learning Units

|

Water lily, Nymphaea ampla, moved onto shore to photograph because there was too much quicksand (silt) and we could not use a tripod out in the river.

|

Sometimes here will be two versions of our reports: a free version that is a photo-essay format; and a Learning Unit version that is part of our long-range training program in digital photography in general, and training for botanical photography in particular. But you don’t have to be a botanist to learn from FLAAR Learning Units: anyone who enjoys doing flower or nature photography can improve their techniques by looking at our examples.

Long range interest in the iconography and biology of the Maya water lily.

Much of my PhD dissertation circa 1985 was focused on the iconography of the water lily. Having a biologist (botanist) in the boat with me during 2007 was more helpful because Mirtha was able to provide a second-opinion as well as look at things through the eyes of a botanist. I tend to look at things though the eyes of an iconographer. By working together we made several breakthroughs in understanding the iconography of this beautiful flower.

Between 2008 and 2013 we undertook additional studies of water lily plants and flowers, especially in Arroyo Pucte (Rio de la Pasion area) and Canal de Chiquimulilla (Monterrico, near Pacific coast). We will be giving two lectures on all our botanical discoveries in two lectures in Antigua Guatemala, 23 October 2015 in the evening and 30 October at 2:30pm.

We hope to find time to publish our findings in the future. But for now, the purpose of this new section on ethnobotany is to let botanists realize that if they need absolutely top professional quality photographs, images that are better than those available in stock photo collections, that FLAAR either has such photos available or can do special photography on commission.

Our photographs are fresh: photos in stock photo collections may be faded because negatives and transparencies naturally fade.

Our photos are digital from the start; photos in stock collections are scanned and thus have visible scanning artifacts. Photos from stock collections are unlikely as well color balanced as we can do today with a gray card.

FLAAR has three Guatemalan biologists on staff; they can survive camping and jungle and hiking. They are bi-lingual or tri-lingual. We also have Mayan speaking assistants. Any or all can be hired through FLAAR for your field trips. Email us at FrontDesk “at” FLAAR.org.

Between the first water lily field trip of 2008 and the most recent expedition (2015) we have several years of several field trips per year of intensive study of water lilies of Peten and Pacific Ocean inland waterways. But most important, we have experimented with different underwater cameras and equipment so we now have an unparalleled reference archive of photographs of the flower most frequently shown in Classic Maya art: the flower of Nymphaea ampla.

|

She is Mirtha Cano (biologist) photographing water lily in your natural habitat. She is using the Canon EOS 5D medium format digital camera. Mirtha has moved on to become a biologist at the Parque Nacional Tikal since this is closer to her family in the San Benito area of Flores.

|

|

Additional photographs added and page updated October 16, 2015

New pictures posted June, 2010

Checked August 24, 2009.

First posted January 2008.

Many years ago, while inspecting a registered private collection in Guatemala (totally registered with the appropriate government institute), I noticed several attractive effigy containers that the owner showed were effigies of guicoy. These Late Classic Maya bowls were quite specifically painted representations of guicoy vegetables. Squash is a common food of the Maya peoples of Guatemala, Belize, Mexico, and adjacent Honduras. Maize, beans, and squash were the traditional foundation of their pre-Hispanic diet.

|

|

|

Guicoy (güicoy), Maya ceramic art of Peten.

|

Yes, the Maya ate root crops, tree fruits and nuts, and we are checking on the possibility that parts of the water lily plant were eaten (they were certainly pictured often in Maya art). But "maize, beans, and squash" was clearly a major part of the diet of the Maya farmers of the last several thousand years. The gardens around their houses, as well as their agricultural fields, still today include maize, beans, and squash.

Guicoy, squash, ayote, calabaza, pumpkin.

You can see the diversity of sizes, shapes, and colors of squash on a web site kcb-samen.ch (Switzerland). There is a thesis from the Universidad San Carlos de Guatemala, "Caracterizacion de 20 cultivares de guicoy…", 1981, 111 pages.

There are as many words for these vegetables as there are species and varieties: Guicoy, güicoy, güicoitos, squash, ayote, calabaza, pumpkin.

|

Ayote (Cucurbita pepo), photo by Jaime Leonardo, FLAAR Photo Archive.

|

Squash as head of decapitated rubber ballgame player in Popol Vuh

Squash is mentioned in the Popol Vuh, as the “replacement head” of the decapitated Hero Twin. We will be referencing this ritual use of squash later during 2015.

Squash in Chilam Balam of Yucatan

We have gone through two of the Chilam Balam books to see how much they discuss plants: either edible or sacred. We will be adding documentation from this research later in 2015.

FLAAR Photo Archive of Maya Ethnobotany.

We have a long range project of professional quality photography of the sacred and utilitarian flowers, fruits, nuts, vegetables, and other plants of the Maya past and present. We just wanted to show some of the first results: taken by Guatemalan biologist Mirtha Cano. Two biologists are on the staff of FLAAR Mesoamerica in Guatemala. Both do botany and zoology of tropical Central America.

|

|

|

|

|

Guicoy (güicoy), photos by Mirtha Cano, FLAAR Photo Archive.

|

|

The pictures to create this QTVR were taken by Jaime Leonardo at La Ruta Maya Conservation Foundation.

|

Bibliography on squash, pumpkins, ayote, etc of Mayan agriculture

Our bibliography web site, www.maya-art-books,org, will have a bibliography on squash within the coming month.

Most recently updated January 19, 2015, while preparing an article on squash for the Institute of Maya Studies (IMS, Miami Science Museum).

Previously updated May 25, 2010 and October 18, 2009.

First posted January 2008.

If you wish to donate your library on pre-Columbian Mesoamerica and related topics, FLAAR will be glad to receive your library and find a good home for it. Contact:

ReaderService@FLAAR.org